Josiah Nott was a leading exponent of polygenism, the belief in the idea of multiple origins of the human species. He was a key figure in the American school of ethnology, which dominated the scientific understanding of race in the decades before Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species appeared in 1859. In 1856 he helped to edit the first American translation of Arthur de Gobineau’s Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines (Essay on the inequality of the human race), a polemical work extolling Teutonic natural supremacy and warning against racial mixing.

In 1854, with George Gliddon, Nott published Types of Mankind, a tribute to their mentor, Samuel G. Morton, and a summation of their evidence that the races were separate and unequal species of Homo sapiens. He was determined to prove his belief in African natural inferiority, informally calling his research “niggerology” and “the nigger business.” The underlying aim was to confound the abolitionists with evidence of the natural and permanent inferiority of blacks, and thus show that their liberation would be a disaster to both races. He asserted that “Caucasians” have been rulers throughout the ages, prepared and destined by nature.

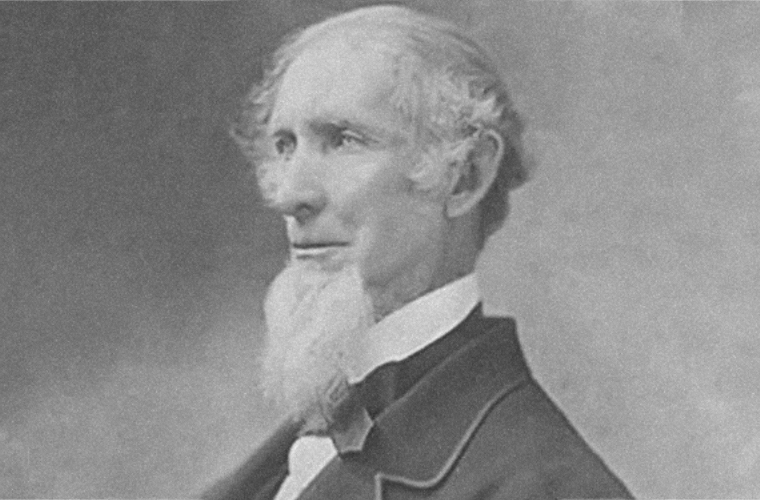

Nott was born in Columbia, South Carolina, on March 31, 1804. He received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania, after which he traveled widely in Europe studying natural history and furthering his medical knowledge. He eventually settled in Mobile, Alabama, and built a flourishing practice treating the slaves of the wealthy. Nott sought to protect his clients, the slaveholders, both politically and scientifically by arguing that blacks and whites were of different species, and that nature itself had preordained their proper relationship to each other. The abolitionists, he claimed, were in error to think otherwise. For Nott, the impure mulatto population was proof of his theory: Being neither black nor white, mulattoes represented a dilution of fixed characteristics unhelpful to either race. This view was in line with several other prominent “ethnologists” of the era who believed that the human species had multiple origins, thus accounting for the diversity of humankind.

Nott had good company in pursuing the polygenist theory: Samuel G. Morton, Ephraim George Squire, James D. B. DeBow, and later Louis Agassiz also championed the fixity of species and the multiple origins of human races. They made this argument from the evidence derived from the study of “hybrids,” crania, Egyptology, and philology. Ignoring the popular slaveholder’s “Hamitic curse” argument for black enslavement, Nott argued that both natural history and slaveholder hegemony constituted evidence in support of his theory.

Nott tried to use scientific debates, lectures, and articles to advance his arguments. Among the scientific opponents of polygenism, the abolitionist churches were certainly united against the theory, as were Professor J. L. Cabell of the University of Virginia, and Rev. John Bachman of Charleston, the latter raising many questions about “exceptional human hybrids” and mixed-race fecundity. Nott dismissed Bachman’s scientific objections as disguised religious positions from a “hypocritical parson,” and he characterized Bachman as a failed scientist and a false minister.

The secular ideology of race was established in the years before Darwin’s work eroded the dominance of polygenism. Nott immediately recognized Darwin’s Origins as finally giving monogenesis an unshakable scientific basis, and in later life he gracefully admitted that Darwin’s answer to the species question had settled the matter of origins, but not the issue of stratified racial diversity. Nott did not abandon his views on race, holding that inequality of status and competence had always characterized black-white race relations.

Having lost two sons in the Civil War, one from wounds received at Gettysburg, Nott could not endure a South transformed, he said, into “Negroland.” He settled in New York City, drawn to a place “without morals, without scruples, without religion, & without niggers.” There he rebuilt his practice, joined Squire’s Anthropological Institute, and flourished until age and health forced his final return to Mobile. He died on March 31, 1873.

Nott’s importance in developing and promoting the theory of polygenism left an enduring legacy of race as a scientific concept. Darwin believed natural selection would cause polygenism “to die a silent and unobserved death” (Darwin 1998 [1874], p. 188), but its supporters continued to justify using race as a secular explanation for human variety. Nott’s work demonstrates how scientific theories often produce definitions of truth that are deeply embedded in the social relations of a given time and space. Nott and his fellow polygenists developed “race” as a construct, the use of which has continued as both a scientific ideology and a common-sense notion, largely due to the influence of Nott.