The Unsung Genius Behind Everyday Innovations

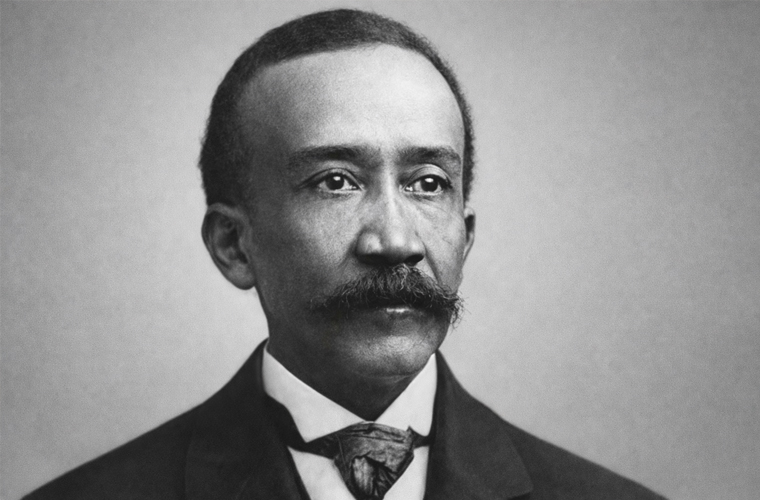

In the annals of American invention, few names evoke the quiet revolution of household ingenuity quite like Samuel R. Scottron. Born in the shadow of slavery’s final gasps and rising to prominence in the post-Reconstruction era, Scottron was more than a tinkerer with mirrors and rods—he was a barber, merchant, educator, and fierce advocate for racial justice. As one of the most prolific African American inventors of the 19th century, his creations transformed ordinary homes, while his activism shaped the fight for equality in Brooklyn’s Black elite circles. This biography explores the life of a man whose legacy endures in the subtle mechanics of our daily lives.

Samuel Raymond Scottron entered the world in February 1841 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to free parents of West Indian descent, with possible ties to the Pequot tribe through his mother’s lineage. His family, seeking opportunity amid the North’s relative freedoms, relocated to New York City in 1849 and settled in Brooklyn by 1852. Scottron’s father juggled roles as a barber, barkeeper, and baggage master on Hudson River boats, instilling in his son a blend of manual skill and entrepreneurial grit.

A bright student, Scottron graduated from grammar school at age 14, though financial constraints delayed further formal education. Undeterred, he pursued night classes and, in a testament to his perseverance, earned a degree in Superior Ability in Algebra and Engineering from the prestigious Cooper Union in 1878 (some records note 1875). These early years honed his mechanical aptitude, setting the stage for a career that bridged trade and innovation.

Civil War Service and Entrepreneurial Beginnings

The American Civil War thrust young Scottron into the fray of history. In 1863, at just 22, he joined his father’s supply firm, Statia, McCaffil, and Scottron, acting as a sutler—providing goods to the 3rd United States Colored Infantry Regiment in South Carolina. The venture proved perilous: storms delayed shipments, and the firm teetered on bankruptcy. Yet, amid the chaos, Scottron witnessed the raw determination of Black soldiers, fueling his lifelong commitment to racial uplift.

Post-war, in 1864, he ventured south to Fernandina, Florida, where he aided newly freedmen in their first elections and represented them at the 1865 National Colored Convention in Syracuse, New York. Seizing the opportunity, Scottron launched a chain of grocery stores across Florida cities like Jacksonville, Gainesville, and Tallahassee. Though profitable initially, the instability of Reconstruction forced their sale, prompting his return north.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, Scottron opened a barbershop—a nod to his father’s trade. Here, necessity birthed genius: frustrated customers struggled to see the backs of their heads in the mirror. Scottron’s solution? A dual adjustable mirror on a standing pole, patented as the “Scottron Mirror” on March 31, 1868 (U.S. Patent 76,253). Marketed with partner Pitkin in New York, it marked his entry into invention, though early setbacks like the Great Chicago Fire tested his resolve.

A Prolific Inventor: Patents That Shaped the Home

Scottron’s workshop became a forge for practical wonders, earning him six U.S. patents that addressed the mundane frustrations of Victorian living. Relocating to New York City, he traded bookkeeping for shop space before establishing his own operation at 211 Canal Street. His inventions included:

- Adjustable Window Cornice (1880): A versatile frame for window treatments, easing installation (U.S. Patent 224,732).

- Cornice (1883): An enhanced decorative molding (U.S. Patent 270,851).

- Pole Tip (1886): A secure cap for curtain poles (U.S. Patent 349,525).

- Curtain Rod (1892): His most iconic creation—a sliding rod for easy shade adjustments, revolutionizing window dressings and still in use today (U.S. Patent 481,720).

- Supporting Bracket (1893): A sturdy holder for poles (U.S. Patent 505,008).

Beyond patents, Scottron’s ingenuity shone in uncredited designs. He developed a “leather hand strap” for trolley passengers during a San Francisco trip and perfected a process to mimic onyx in glass, licensing it to Connecticut firms for lamps and candlesticks. As a traveling salesman for John Kroder’s export firm from 1882, he peddled his wares across Canada and the northern U.S., amassing a fortune that peaked at $60,000 in property. His essay “Manufacturing Household Items” in The Colored American Magazine (1904) chronicled these triumphs, blending technical detail with pride in Black enterprise.

Civic Leader and Racial Advocate

Scottron’s impact extended far beyond patents. A staunch Republican, he co-founded the Cuban Anti-Slavery Society in 1872 with Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, later expanding it to combat bondage in Puerto Rico. In 1884, he established the Society of the Sons of New York, fostering Black mutual aid. As a 33rd-degree Mason and Grand Secretary General of its Supreme Council, he wielded influence in fraternal networks.

Education became his battleground in 1894, when he joined Brooklyn’s Board of Education as its sole African American member—a post he held for eight years. Scottron championed better facilities for Black students, clashing with reformers like Mayor Seth Low, who ousted him in 1902 amid debates over segregated schools. He lectured widely, amassed a library on African American history, and penned incisive articles for outlets like the New York Age and Colored American, decrying job displacement in trades like barbering. Booker T. Washington immortalized him in The Negro in Business (1907), hailing Scottron as a model of self-made success.

Personal Life and Enduring Legacy

In 1863, Scottron wed Anna Maria Willett, a Peekskill, New York native of Algonquian descent, in a union that produced six children—three daughters and three sons. The family, devout Episcopalians, worshipped at St. Philip’s in Manhattan and St. Augustine’s in Brooklyn. By 1888, they owned a brownstone in Brooklyn’s elite Black enclave. Their youngest son, Cyrus, fathered entertainer Lena Horne, making Scottron her great-grandfather—a lineage detailed in Gail Lumet Buckley’s The Hornes: An American Family.

Scottron’s life closed on October 14, 1908, at age 67, from natural causes in his Brooklyn home. Survived by his family, he left a blueprint for Black excellence: innovate relentlessly, advocate unyieldingly, and build communally.

Today, Scottron’s curtain rods shade windows worldwide, his mirrors reflect countless faces, and his story inspires a new generation. In an era that often erased Black contributions, Samuel R. Scottron proved that true progress hangs on the smallest pivots—and the boldest visions.