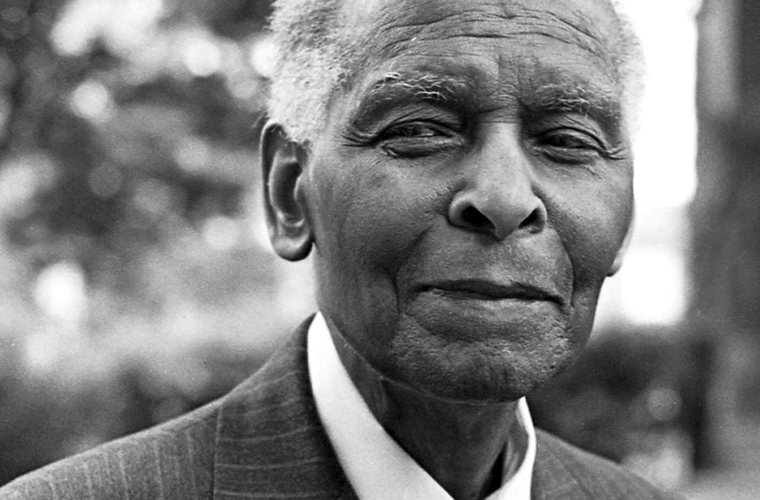

Perhaps best known as the longtime president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Benjamin Mays was a distinguished African American minister, educator, scholar, and social activist. He was also a significant mentor to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and was among the most articulate and outspoken critics of segregation before the rise of the modern civil rights movement in the United States. Mays also filled leadership roles in several significant national and international organizations, among them the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the International Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the World Council of Churches, the United Negro College Fund, the National Baptist Convention, the Urban League, the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, the Southern Conference Educational Fund, and the Peace Corps Advisory Committee.

Education

Benjamin Elijah Mays was born on August 1, 1894, or 1895 in a rural area outside Ninety-Six, South Carolina. He was the youngest of eight children born to Louvenia Carter and Hezekiah Mays, tenant farmers and freedpeople. A consistent theme in Mays’s boyhood and early adulthood was his quest for education against overwhelming odds. He refused to be limited by the widespread poverty and racism of his place of birth. After some struggle, he gained acceptance to Bates College in Maine. After completing his B.A. there in 1920, Mays entered the University of Chicago as a graduate student, earning an M.A. in 1925 and a Ph.D. in the School of Religion in 1935.

Career and Accomplishments

Mays’s education in Chicago was interrupted several times, first by stints as a teacher at Morehouse and at South Carolina State College. During his tenure at the latter, he met his future wife, Sadie Gray. They were married for forty-three years, from 1926 until her death in 1969. Mays’s work for the Urban League and the YMCA similarly postponed his doctoral efforts. In 1933, with coauthor Joseph Nicholson, Mays published a groundbreaking study entitled The Negro’s Church, which describes the unique origins and character of this central African American institution, offering a critique of some of its problematic clerical practices.

Less than a year before completing his dissertation at Chicago in the spring of 1935, Mays accepted a position as dean of the School of Religion at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Mays distinguished himself as an effective administrator, elevating the Howard program to legitimacy and distinction among schools of religion. During his tenure there, Mays also traveled a great deal, which would become a consistent aspect of his career. Perhaps the most significant of these travels was a trip in 1936 to India, where he spoke at some length with Mahatma Gandhi, anticipating an exchange of ideas that would come to fruition during the civil rights movement some years later. Mays also continued his scholarly efforts. In 1938 he published The Negro’s God, as Reflected in His Literature, a study of the image and concept of God in African American Christianity.

In 1940 Mays became the president of Morehouse College. There he rose to national prominence, enjoying great influence on key events in U.S. history. His most famous student at Morehouse was Martin Luther King Jr. During King’s years as an undergraduate at Morehouse in the mid-1940s, the two developed a close relationship that continued until King’s death in 1968. Mays’s unwavering emphasis on two ideas in particular—the dignity of all human beings and the incompatibility of American democratic ideals with American social practices—became vital strains in the language of King and the civil rights movement. Although Mays’s essays and sermons throughout his years at Morehouse related these ideas, their clearest explication came in his book Seeking to Be a Christian in Race Relations, published in 1957.

As an administrator at Morehouse, Mays expanded and streamlined the structure of the institution and enhanced its academic reputation. He was a highly successful fund-raiser, securing the needed financial support for Morehouse to pursue its educational goals. Beyond such practical concerns, Mays left a legacy of prominent Morehouse graduates and lent the college his own inimitable style, characterized by rigor and enthusiasm for the Morehouse mission.

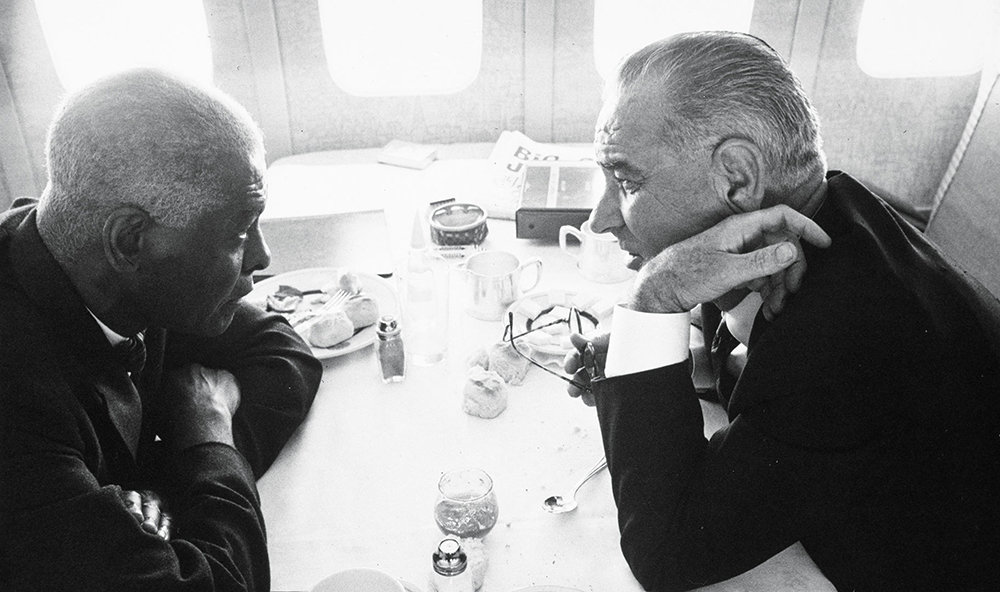

After his retirement in 1967 from Morehouse, Mays remained active in several social and political organizations of prominence and was in demand as a speaker and lecturer. As the school board’s first Black chair, he oversaw the desegregation of the Atlanta public schools between 1970 and 1981. He also published two autobiographies in these years, Born to Rebel (1971) and Lord, the People Have Driven Me On (1981). He died in 1984.