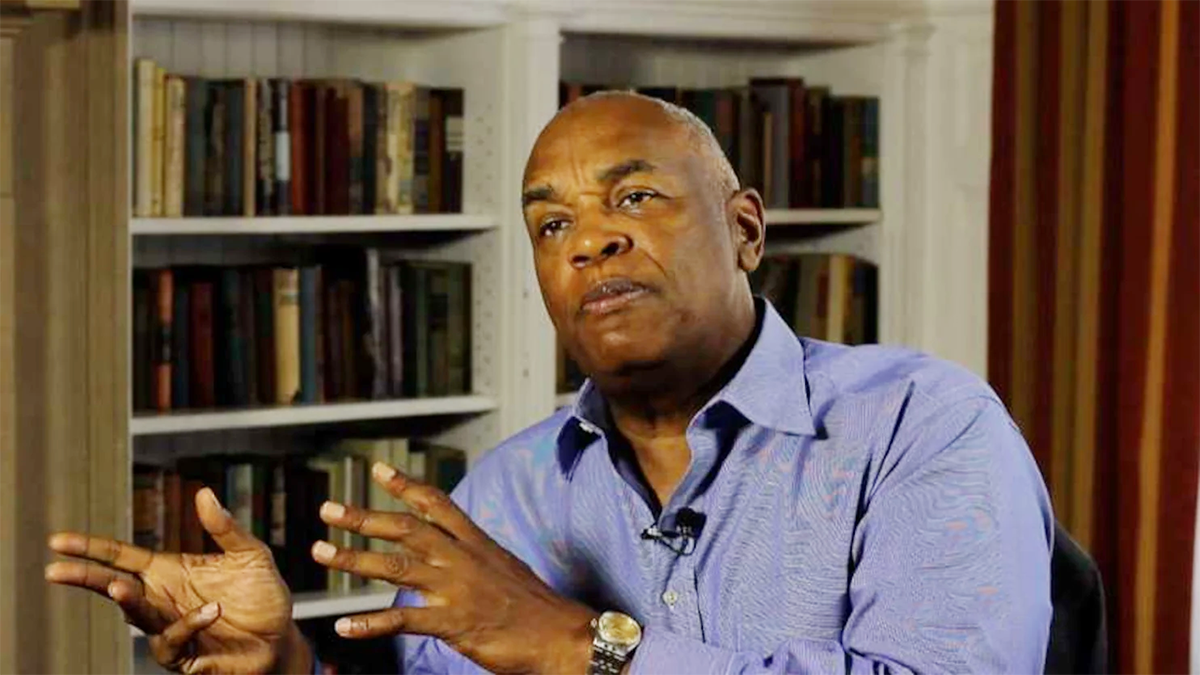

Courtland Cox spent his childhood between New York City and Trinidad. Education was important to his family, and they sent him to St. Helena’s Catholic School where for one year, he was the only Black student. When Cox arrived at Howard University in 1960, he joined the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), already committed to fighting segregation and white supremacy. Cox met classmates like Stokely Carmichael, Ed Brown, Michael Thelwell, Jean Wheeler, and others as NAG became involved in sit-ins along Route 40, Freedom Rides, and demonstrations on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

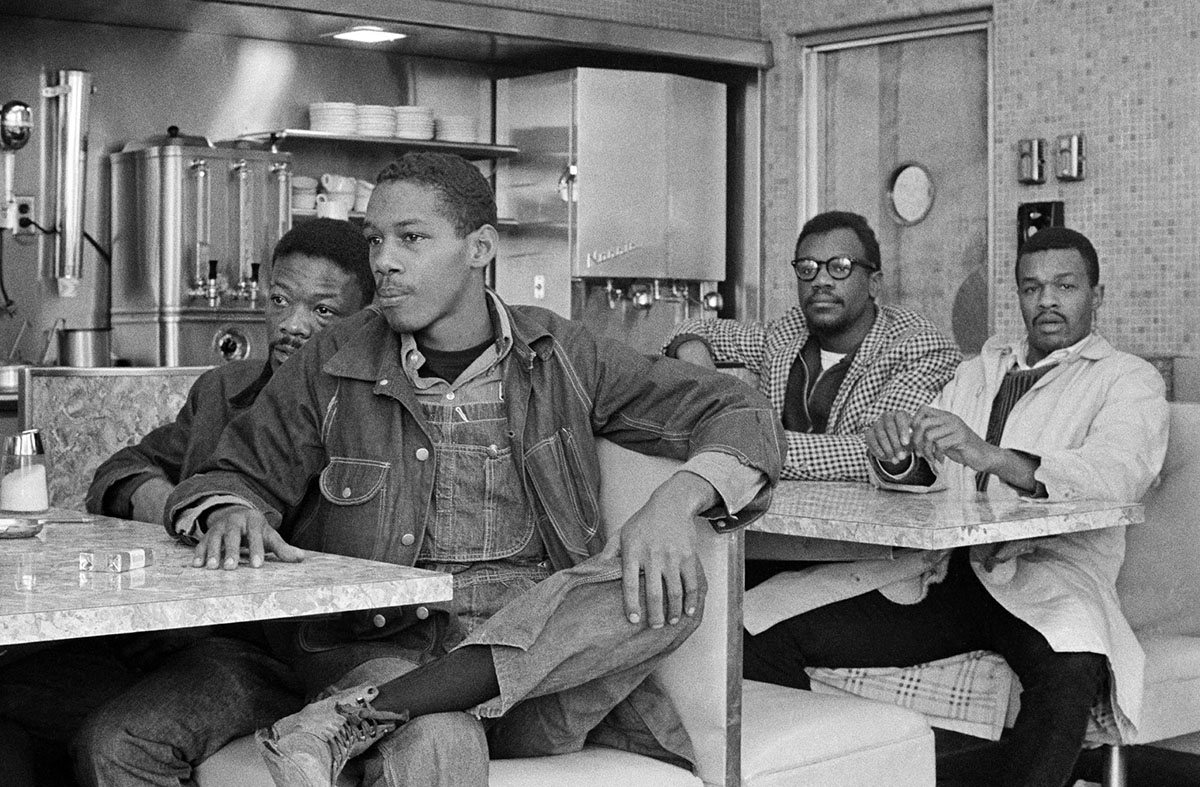

In its early days, SNCC operated as a loose association of student groups, and Cox was one of NAG’s representatives on SNCC’s coordinating council. The “interminable” SNCC meetings in Atlanta centered on figuring out how a situation could be changed instead of solely questioning why it existed. Cox began exploring strategies and tactics beyond protest. Like many in NAG, he was greatly influenced by Bayard Rustin, who came on and off Howard’s campus because of NAG’s activism, most notably in 1962 for a debate Malcolm X sponsored by a campus group Cox had helped organize: Project Awareness.

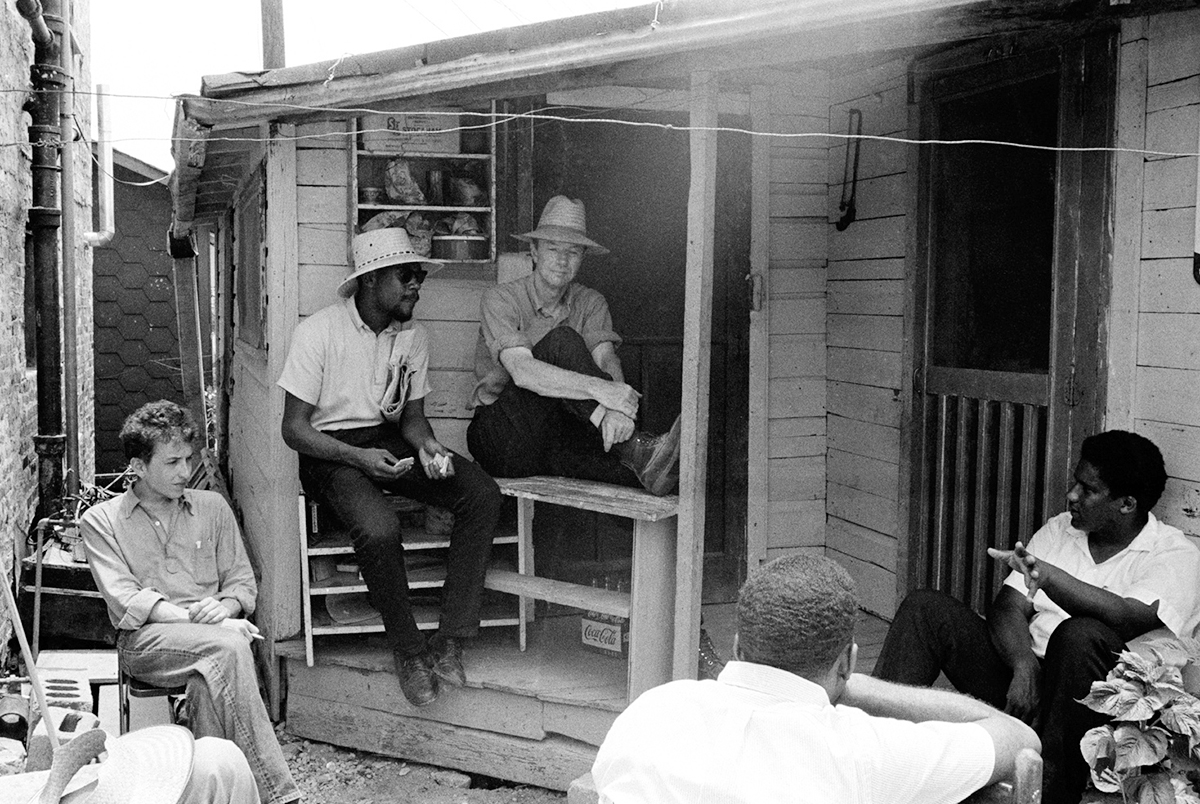

The betrayal of the MFDP at the 1964 Democratic National Convention confirmed Cox’s view that an independent Black political party was necessary. He left Mississippi after the challenge and joined Stokely Carmichael in Lowndes County, Alabama, known then as “Bloody Lowndes” for its anti-Black violence. When Cox started working in Lowndes, Blacks made up 80% of the country’s population, but only four black people were registered to vote. After the Voting Rights Act passed, SNCC helped register 2,800 voters, and for the first time, there were more registered Black voters than white voters in the county.

But Cox and the other SNCC organizers thought it was not enough for Black people to vote for a less racist white sheriff; they wanted local people to elect county officials who shared their concerns. “It’s not about protest it’s about power,” explained Cox. Why protest about police brutality by the sheriff when Black people could elect a sheriff that reflected their interests?

SNCC researcher Jack Minnis found an obscure Alabama law that allowed for the creation of county-level political parties. It gave Cox and the SNCC organizers ammunition they needed to organize the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP), an independent, Black political party. In Alabama, local parties were required to have a visual symbol because of the state’s high illiteracy rate. The LCFO chose a black panther. It was quickly embraced by the county’s Black community as representing the power that SNCC was helping them reclaim.

Later, Cox became SNCC’s program coordinator, and in 1967 traveled to Stockholm to represent SNCC at the Bertrand Russell International War Crimes Tribunal. SNCC had come out against the Vietnam War in January 1966, because after years of organizing, they now questioned why young Black men should fight and die in Vietnam when they were denied first-class citizenship and faced white supremacist violence at home.

Cox remained committed to the idea of economic empowerment. Black communities, he noted, whether in the Deep South or northern cities, lacked “any kind of economic infrastructure that could make a difference,” and Atlantic City had helped him realize that “you could not keep asking people … who were in fact benefitting from the status quo to change the status quo.”

He saw the possibility of building alliances across the Black Diaspora, and in 1974, he helped organize a Sixth Pan African Congress in Tanzania that brought together Black leaders from around the world to discuss the “rekindling of political understanding and cooperation among African people.”