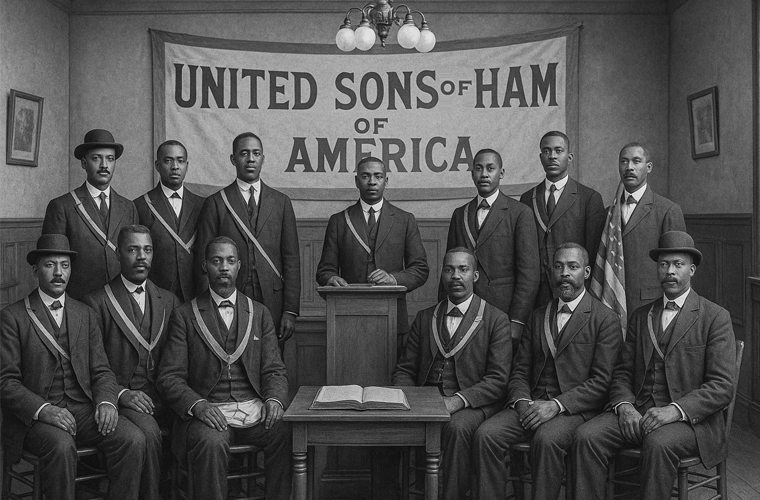

A Pillar of African American Fraternal Life During Reconstruction

During the turbulent era of Reconstruction following the American Civil War, African American communities in the South faced immense challenges in rebuilding their lives amid widespread poverty, discrimination, and the lingering scars of enslavement. In this context, fraternal and benevolent societies emerged as vital institutions, offering mutual aid, social solidarity, and a semblance of autonomy in a hostile environment. Among these was the United Sons of Ham of America (USH), also known simply as the Sons of Ham, a prominent African American secret society that flourished particularly in the Southern states. Founded in the immediate aftermath of emancipation, the USH exemplified the resilience and communal spirit of newly freed Black Americans, providing not just practical support but also a framework for moral upliftment and collective empowerment.

Origins and Early Development

The exact origins of the United Sons of Ham remain somewhat shrouded in historical ambiguity, with no definitive record pinpointing a single founding moment or location. However, archival evidence suggests the society took root in several Southern states, including Arkansas, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, likely emerging organically in response to the urgent needs of emancipated communities. One of the earliest documented chapters was established in Little Rock, Arkansas, on October 7, 1865—just months after the war’s end—marking it as the city’s inaugural Black benevolent fraternal organization. This chapter began modestly with just twenty members, who gathered in a simple wood-frame building for their initial meetings. The group’s rapid growth reflected the broader surge in Black mutual aid societies during Reconstruction, as freedpeople sought to create spaces for self-governance and support outside the control of white authorities.

Over time, the USH expanded, with branches appearing in other Arkansas locales such as what is now North Little Rock, Searcy, Fort Smith, and Pine Bluff. By the early 1870s, the Little Rock chapter alone boasted around seventy-five members, primarily men aged eighteen to fifty, and the society endured for nearly two decades before gradually fading. Interestingly, different chapters may have commemorated their foundings on varying dates, underscoring the decentralized nature of the organization; while Little Rock observed its anniversary in October, the Memphis, Tennessee, branch celebrated its thirteenth year on July 4, 1872.

The society’s infrastructure evolved in tandem with its membership. In Little Rock, the group outgrew its first modest venue and constructed a three-story brick building on the west side of Broadway, between 8th and 9th streets, adjacent to the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. The upper floors served as lodge halls for meetings and rituals. At the same time, the ground level initially housed Howard School—a short-lived educational initiative named after Oliver O. Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner. Leased to the Little Rock School Board for three years, the school was led by principal Samuel H. Holland, with notable educator Charlotte Andrews (Lottie) Stephens serving as a teacher until 1870, when she departed to study at Oberlin College in Ohio. After the school’s closure in late 1871, the first floor transformed into a public hall, hosting community events and affairs central to Black civic life.

Purpose and Guiding Principles

At its core, the United Sons of Ham was a benevolent society dedicated to fostering industry, brotherly love, and charity among its members. It provided essential mutual aid, such as financial assistance to the widows and orphans of deceased members, burial benefits, and even dedicated cemetery plots—such as the “Sons of Ham section” in Little Rock’s Oakland Cemetery, secured after persistent advocacy in 1888 alongside other Black organizations like the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. The group enforced a rigorous moral code, prohibiting gambling and drinking to promote personal discipline and communal harmony.

As historian Adolphine Fletcher Terry later observed in her descriptions of the society’s rituals, enslavement had systematically denied Black people educational opportunities and the freedom to assemble, deliberately sowing division to maintain control. The USH sought to counter this legacy by uniting a fragmented people and equipping them to thrive as productive citizens in a post-slavery society. Charlotte Andrews Stephens echoed this sentiment, portraying the organization as a crucial tool for the “development of a newly emancipated people,” despite fierce rivalries with competing fraternal groups like the Prince Hall Masons.

Though the USH officially declared itself non-political—a prudent stance in an era of violent white backlash against Black advancement—its activities often blurred these lines. The 1871 annual convention in Little Rock, for instance, mirrored a state legislative session, complete with introduced “bills,” debates, and impassioned speeches. Many members doubled as influential community leaders and elected officials, including street commissioners, policemen, and legislators, amplifying the society’s role in grassroots politics.

The Enigma of the Name

The choice of “Sons of Ham” for the society’s name draws from biblical lore, specifically the Book of Genesis, where Ham—one of Noah’s sons—is depicted as the progenitor of African peoples through his descendants: Cush (often associated with Ethiopia), Mizraim (Egypt), Phut (Libya), and Canaan. Early religious interpretations, prevalent in 19th-century America, linked Ham’s lineage to Black Africans, sometimes invoking the so-called “Curse of Ham“—a misreading of Noah’s curse on Canaan (Genesis 9:20-27)—to rationalize enslavement. Paradoxically, the USH reclaimed this narrative, transforming a tool of oppression into a symbol of shared heritage and pride. While the precise reasoning behind the name remains speculative, it likely served to instill a sense of ancient dignity and collective identity among members navigating the indignities of Reconstruction.

Celebrations, Rituals, and Community Impact

The USH infused its mission with vibrant traditions that strengthened bonds and asserted cultural presence. Founding anniversaries were marked with elaborate fanfare each October, featuring lively parades, stirring music from brass bands, eloquent guest speakers, lavish banquets, and communal gatherings that drew thousands. Key national dates held sacred status: Emancipation Day on January 1 and Independence Day on July 4 were mandatory public observances, with the society often spearheading citywide events. In September 1871, for example, the Sons of Ham joined forces with Prince Hall Masons and other fraternities for a grand procession honoring the Emancipation Proclamation’s anniversary and the Bethel AME Church cornerstone laying. Dressed in dark blue sashes, members marched solemnly, with renowned orator William H. Grey delivering the keynote address; a copy of the society’s history was reportedly sealed in the cornerstone. Grey returned as speaker for the group’s July 4 celebration in 1873.

Funerals underscored the society’s solemn commitments, with processions featuring horse-drawn hearses adorned in black plumes, accompanied by mournful bands. Meetings and banquets were frequently convened at Bethel AME, where overlapping memberships fostered synergies. Women’s auxiliaries, known as the Daughters of Ham or Ladies Court of the Daughters of Ham of America, existed in places like Pine Bluff, enabling female involvement in social planning, though no formal chapter is recorded in Little Rock.

The USH also intersected with broader fraternal networks. In 1873, three Prince Hall Masonic lodges convened in the Sons of Ham Hall to establish the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Arkansas, highlighting the building’s role as a hub for Black organizational life.

Leadership and Legacy

Early leadership reflected the society’s ties to military and civic service. Founder Emmanuel Aiken, a Civil War veteran who rose to corporal in the Eleventh Regiment, United States Colored Infantry (later the 113th), transitioned postwar into roles as a Little Rock policeman, street commissioner, and pension agent. Subsequent presidents from 1870 to 1876 included Henry H. Powers (another street commissioner), educator James W. Jackson, policeman Isaac Singleton, and Samuel L. White, who served multiple terms and remained active until he died in 1895. Many leaders are interred in the society’s Oakland Cemetery plot, a testament to enduring ties.

The USH’s decline is as gradual as its rise, likely attributable to the aging out of founding members (due to the fifty-year age cap), competition from national rivals like the Masons and Odd Fellows, and the intensifying Jim Crow oppression. It persisted at least until 1888, when it lobbied for cemetery land, but by the late 1880s, it had largely dissolved. Nonetheless, its legacy endures as a model of Black self-reliance, weaving threads of mutual support, cultural reclamation, and quiet resistance into the fabric of Reconstruction history. In an age that sought to relegate freedpeople to the margins, the United Sons of Ham stood as a beacon of unity and aspiration, reminding us of the profound ways communities forged hope from adversity.