What actually happened when the slaves in America were freed? It didn’t all happen at once, so it’s not like trying to picture what, say, the surrender of General Lee was like. There are plenty of accounts of that specific incident. But the emancipation of black slaves in the United States wasn’t that simple (as this timeline indicates). The end of the war on April 9, 1865, is just one of many instances of the “freeing of the slaves.” There were other occasions, depending on where you lived (slavery was abolished in Washington, D.C., in 1862, for example).

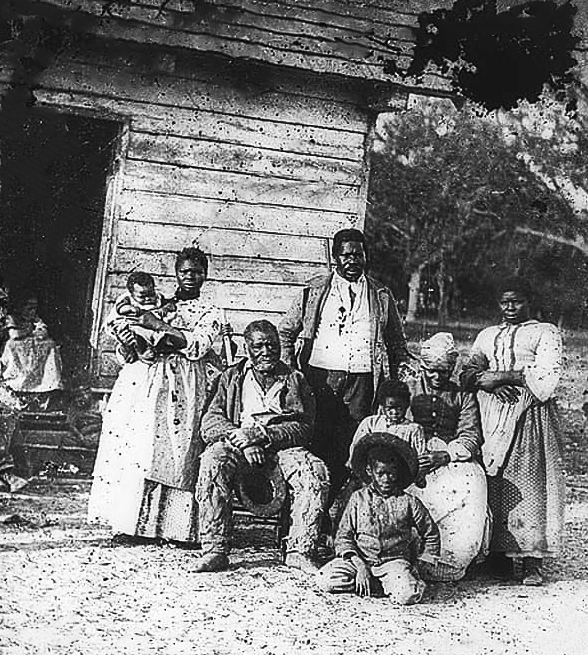

So this list features first-hand accounts of what happened once the slaves were freed at plantations and farms across the United States, on the day of their emancipation, whatever that particular date may be. Want to really know how the freeing of the slaves worked? How did it feel? Below is just a small sampling of the words of the millions of men, women, and children that actually lived through it.

Some Emancipated Slaves Decided to Remain on the Plantation

Booker T. Washington mentions in his autobiography that many ex-slaves—especially older ones—worked out deals to stay on their plantations and work for their former masters for pay even after they were legally free. Even on their first day of freedom, Washington notes that “one by one, stealthily at first, the older slaves began to wander from the slave quarters back to the ‘big house’ to have a whispered conversation with their former owners as to the future.”

Like Washington, Thomas Rutling was only nine years old when he and his fellow slaves on a plantation in Wilson County, TN learned about their emancipation. Rutling thought the freedom would mean a life like that of his former master, but his family chose to stay on the plantation for two more years:

One night the report of Lincoln’s Proclamation came. Now, the master had a son who was a young doctor. I always thought him the best man going: he used to give me money and didn’t believe much in slavery. The next morning I was sitting over in the slave quarters, waiting for breakfast, when the young doctor came along and spoke to my brother and sister, at the front door. I supposed it was about work, but they jumped up and down, shouted, sang, and then told me I was free. I thought that was very nice; for I supposed I should have everything like the doctor and decided in a moment what kind of a horse I would ride. We remained on the plantation until 1865.

Ruling left the plantation with his brother and sister that year to live with their oldest sister in Nashville, later attending the Fisk Free Colored School, which later became Fisk University.

Whether Freedmen and Women Left or Stayed Often Depended on Their Age and Health

Ex-slave Annie L. Burton, in her Memories of Childhood’s Slavery Days (1909), wrote about all of her fellow ex-slaves on a plantation near Clayton, AL, that wasn’t “feeble or sickly” left “upon the news of their freedom” in April 1865. Annie and her young sisters stayed under the care of their “mistress” (who, by the way, tried to talk her husband into not telling the slaves about their freedom) because their mother ran away. The “feeble or sickly” ex-slaves that remained helped to gather the crops and take care of the plantation.

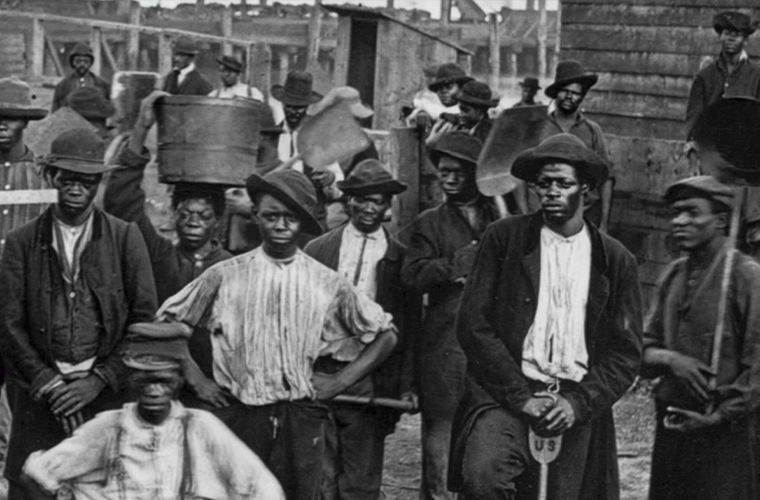

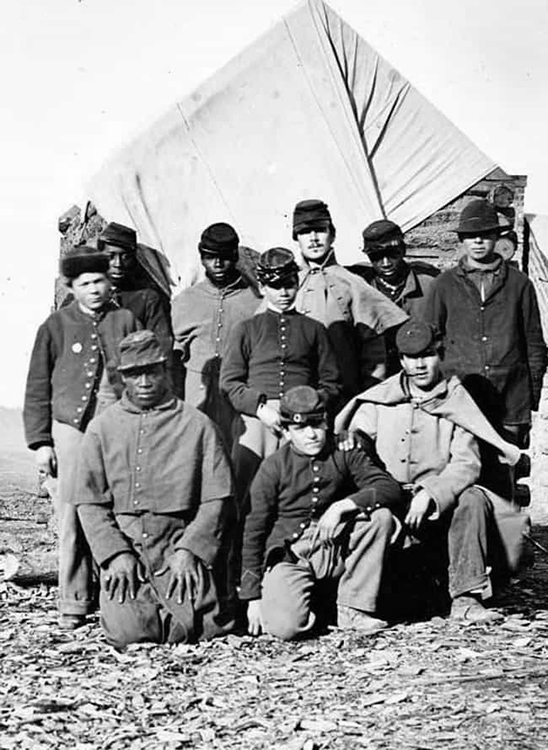

There are similar accounts from the Federal Writer’s Project Slave Narratives. Some young, healthy ex-slaves immediately volunteered to join the Union army. Many older ex-slaves stayed behind, such as John Love of Texas, who explained, “De plantations all grown up in weeds and all de young slaves gone, and de ones what stayed was de oldest and most faithful.”

Many Freedmen and Women Were Asked to Sign ‘Work Contracts’

Not content with handshake deals, some plantation owners in April 1865, when the crops were planted and growing nicely, asked their ex-slaves to sign contracts guaranteeing that they would work the crops until January, then divide them at the fall harvest for payment. Rev. Irving E. Lowery’s Life on the Old Plantation in Ante-Bellum Days, or, A Story Based on Facts (1911) mentions such a deal. To help convince them, Lowery’s ex-master Mr. Frierson made a long speech on April 9 reminding his now ex-slaves that he wasn’t that bad of a guy and they could all stay as long as they wanted:

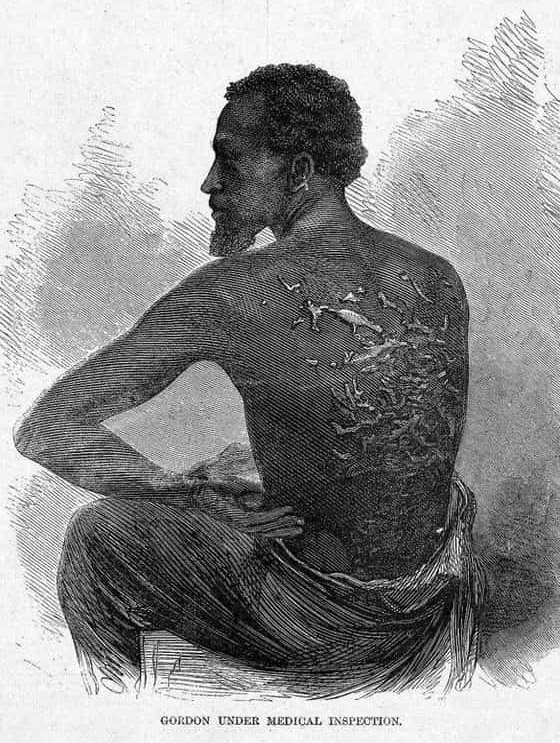

There is another thing which I want to call your attention to. I have never put an overseer over you, neither have I employed a “n***** driver” on my plantation. I have owned no bloodhounds, and have not given any encouragement, nor employment to those who have owned them. I have never separated, by selling nor by buying, a mother and her child; a husband and his wife. Of the truth of this, you will bear me witness. In all these matters, I have the approval of a good conscience.

Frierson also made sure to let his ex-slaves know that any mistreatment they experienced outside the plantation was their fault, not his:

But some of you have gone off without my knowledge, and without a ticket, and have been caught and whipped, but it was not my fault. I was not to blame for that. You, yourselves, were responsible for it.

Ultimately, all but one ex-slave agreed to “sign” the contract by lining up to touch a pen held over the paper to make a small mark upon it, in lieu of a signature.

Henry Clay Bruce Agreed to Stay and Work for His Former Master but Was Never Paid

Reading The New Man: Twenty-Nine Years a Slave, Twenty-Nine Years a Free Man(1895), the memoirs of ex-slave Henry Clay Bruce, reveals that the relationship between ex-master and ex-slave at the point of emancipation was sometimes pretty pathetic—in the oldest sense of the word. Bruce’s old master, for example, practically begged his ex-slaves to stay:

Our owner did not want us to leave him and used every persuasive means possible to prevent it. He gave every grown person a free pass and agreed to give me fifteen dollars per month, with board and clothing, if I would remain with him on the farm, an offer which I had accepted to take effect January 1, 1864.

But by March of that year I saw that it could not be carried out, and concluded to go to Kansas. I might have remained and induced others to do so and made the crop, which would have been of little benefit to him, as it would have been spirited away. I made the agreement in good faith, but when I saw that it could not be fulfilled had not the courage to tell him that I was going to leave him.

Bruce says that years later he checked in on his old master, through visits and letters, learning about the increasingly sad conditions at the farm, including tales of stolen horses and feed.

A Former Slave Owner Became ‘Irrational and Childish’

Former slaves Sam and Louisa Everett told Federal Writers’ Project interviewer Pearl Randolph in 1936 about the behavior of their former owner, “Big Jim” McClain of Norfolk, VA, when he learned his slaves were legally free. It’s just one example, according to Catherine A. Stewart’s Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project, of how slave owners “exhibited a variety of irrational and childish behaviors” upon hearing the news. Here’s Randolph’s description of the day “Big Jim” had to face the facts, based on her interview with Sam and Louisa Everett:

” Big Jim” stood weeping on the piazza and cursing the fate that had been so cruel to him by robbing him of all his “n*****s.” He inquired if any wanted to remain until all the crops were harvested and when no one consented to do so, he flew into a rage; seizing his pistol, he began firing into the crowd of frightened Negroes. Some were killed outright and others were maimed for life. Finally, he was prevailed upon to stop. He then attempted to take his own life. A few frightened slaves promised to remain with him another year; this placated him. It was necessary for Union soldiers to make another visit to the plantation before “Big Jim” would allow his former slaves to depart.

One Former Slave Owner Let the Whole Plantation Get Drunk and Party

Charles Hays was a slave owner with a plantation located sixteen miles north of Louisville, KY. Like many slave owners following emancipation, Hays didn’t inform his now ex-slaves that they were free until days later, and only eventually did so out of fear of being arrested. Here’s how ex-slave Harry Smith says Hays finally broke the news, according to his Fifty Years of Slavery in the United States of America (1891):

[Hays said,] “Men and women hear me, I am about to tell you something I never expected to be obliged to tell you in my life, it is this: it becomes my duty to inform you, one and all, woman, men, and children, belonging to me, you are free to go where you please.” At the same time [he was] cursing Lincoln and exclaiming, if he was here, I would kill him for taking all you negroes away from me.

After Hays cooled down “from this painful duty,” he let the entire plantation have access to the whiskey stash, leading to what sounds like a pretty amazing party:

Then commenced a great jubilee among, not only the slaves, but old Massa, and all on the plantation seemed to join in the festivities. Old Massa got drunk and repaired to his room. His daughter, a fine young lady never known to drink, was much the worse for drinking. All were cheering Abraham Lincoln, while old Massa was too drunk to notice much.

Old Aunt Bess an old colored woman, and very religious, who looked after the children, as well as the rest, used too much wine and to show her mode of rejoicing, sang old-time songs, which added very much to the celebration. Preparations were made and at night dancing began in earnest and kept up until morning.

Some Former Slave Owners Hid the Truth

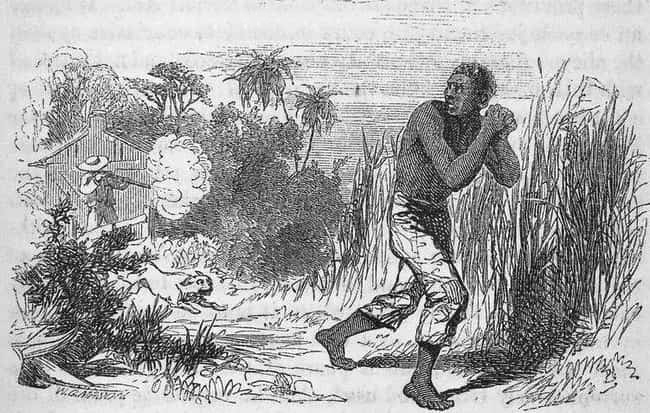

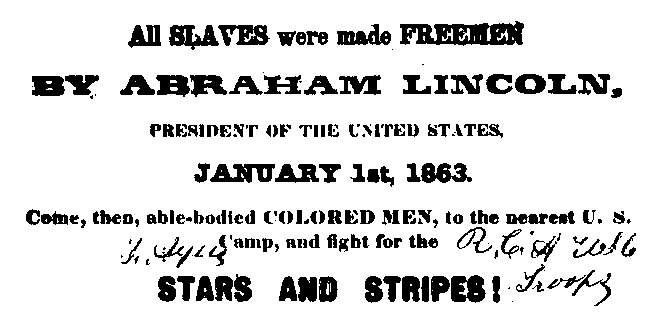

As the Civil War Diary of James T. Ayers reveals, some slave owners simply didn’t tell their slaves that they were legally free. Professor Matthew Pinsker from Dickinson College says Ayers was one of more than 200 Union recruiters that went into the South to enlist newly freed men for the Union cause—and sometimes be the first to inform them that they were, in fact, free men and women.

One diary entry from May 7, 1864, details Ayers spreading the word of emancipation to a group of ex-slaves on the John Eldridge plantation near Huntsville, AL. He showed them a broadside featuring an illustration of freed slaves on one side and a two-sentence version of the Emancipation Proclamation on the other. Here’s his pitch (spelling and punctuation corrected):

“We need some help. [The Union] offers ten dollars a month and [will] clothe you and feed you and make you free if you will enlist and be soldiers. How many of you boys will turn out?” “When do you want us, Massa?” “Want you right now.” “Oh, Massa won’t let us go.” “Never mind your master – you have none. I’ll see to that your master shan’t hinder you.”

Ayers says that four men agreed to enlist, so he told them to gather their things, promising he would protect them. When confronted by John Eldridge and his family, Ayers stood firm:

“What’s all this mean? My n*****s say you came into the field and set them all free. Is that so?” “Yes, sir.” “Well, I would like to know how you got the authority to do so, sir.” “By the War Department, sir, I get my authority – the very best of authority, ain’t it?” “What do you want with my n*****s?” says he. “Your n*****s? You’ve got no n*****s, my dear sir. These are all free men …”

Ayers drew his “trusty revolver out of scabbard” to end the debate, telling Eldridge, “I shall not hurt a hair of your head, sir, if you be quiet, but I have come for your darkies and your darkies I’ll have.” (Sounded like a modern-day action hero until the “darkies” bit, eh?)

Pinsker says that Ayers “recruited hundreds of black soldiers and spread the word of emancipation to thousands of former slaves” before his death “from disease” in September 1865.

Some Former Slave Owners Just Called a Meeting

At the Virginia plantation where Booker T. Washington was born, the first official day of freedom began with a simple, solemn meeting, followed by a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by a government official. Washington was approximately nine years old that day (there are no official records of his birth). As his account in his autobiography Up From Slavery (1901) details, the news was initially met with much celebration among the now-former slaves:

The night before the eventful day, the word was sent to the slave quarters to the effect that something unusual was going to take place at the “big house” the next morning. There was little, if any, sleep that night. All was excitement and expectancy. Early the next morning word was sent to all the slaves, old and young, to gather at the house. In company with my mother, brother, and sister, and a large number of other slaves, I went to the master’s house. All of our master’s family were either standing or seated on the veranda of the house…As I now recall the impression they made upon me, they did not at the moment seem to be sad because of the loss of property, but rather because of parting with those whom they had reared and who were in many ways very close to them… After the reading [of the Emancipation Proclamation] we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see. For some minutes there was great rejoicing, and thanksgiving, and wild scenes of ecstasy. But there was no feeling of bitterness. In fact, there was pity among the slaves for our former owners.

Washington says that the ecstasy was soon tempered by worry about what freedom really meant:

The wild rejoicing on the part of the emancipated colored people lasted but for a brief period, for I noticed that by the time they returned to their cabins there was a change in their feelings. The great responsibility of being free, of having charge of themselves, of having to think and plan for themselves and their children, seemed to take possession of them…To some, it seemed that, now that they were in actual possession of it, freedom was a more serious thing than they had expected to find it. Some of the slaves were seventy or eighty years old; their best days were gone. They had no strength with which to earn a living in a strange place and among strange people.

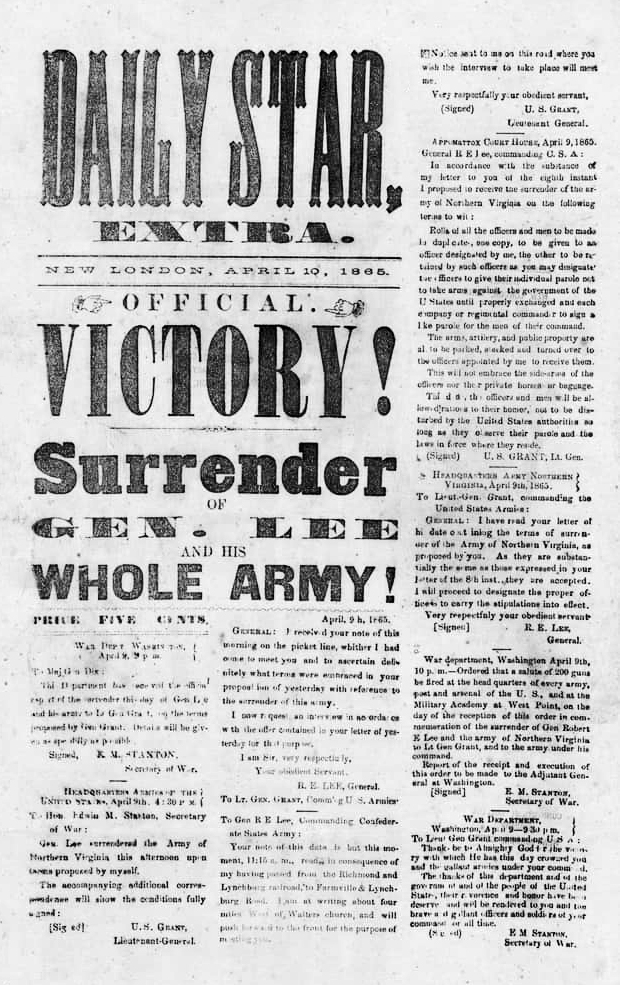

Tasswood Ward Read His Former Slaves the Newspaper

In The Memoirs of Samuel Spottford Clement Relating Interesting Experiences in Days of Slavery and Freedom (1908), Clement says that his ex-master, Tasswood Ward, read to him and the other ex-slaves on Ward’s plantation in Campbell County, VA, from the newspaper the morning of April 12, 1865 (three days after General Lee surrendered), to inform them they were free:

Mr. and Mrs. Ward came out, she crying, and Mr. Ward holding a newspaper walked to the front of the steps and said (instead of saying as of years gone by “negroes”), “Men and women you are as free as the birds that fly in the air.” He raised the paper to his face and read in substance as follows: “General Lee today has surrendered to General Grant. General Grant had six months’ rations while General Lee had only three days’ rations for his starving troops. So the Southern Confederacy is now at an end and all negroes are free.”

Ward then offered to pay the men to stay and reap the crops, an offer accepted by all but one man, known only as Uncle Fendall, who was worried that the “rebs might go back fighting again” and ruin his chance at freedom, which “he done prayed for all his life.”

Some Former Slave Owners Offered Advice

Thomas Almond Ashby was 17 years old when he witnessed his father inform the family’s slaves on their plantation in Front Royal, VA, that they were now free. In his memoir The Valley Campaigns (1914), Ashby says that his family had a “feeling of kindest respect” for their slaves, a feeling which Ashby claims was reciprocated. Here is what Ashby’s father said that day:

He told them that he had no further control over them, that in the future he would pay them for services such as wages as would be established in the community, and that if they wished to remain in his employ they could do so as long as they desired; but that if any of them wished to find new homes, they were at liberty to make a change. He assured them of his friendly interest in them and of his desire to see them do well and be happy. He told them of the altered conditions that would surround them under freedom and urged them to cultivate habits of thrift and industry, which would make them useful citizens and self-respecting men and women.

According to Ashby’s account, it took “several years” before all of the ex-slaves left the plantation. A woman known only as “Aunt Susan” seemed to take the advice to heart: after saving for three years “by taking in the washing and doing light work,” she bought a “neat little house” in the city.