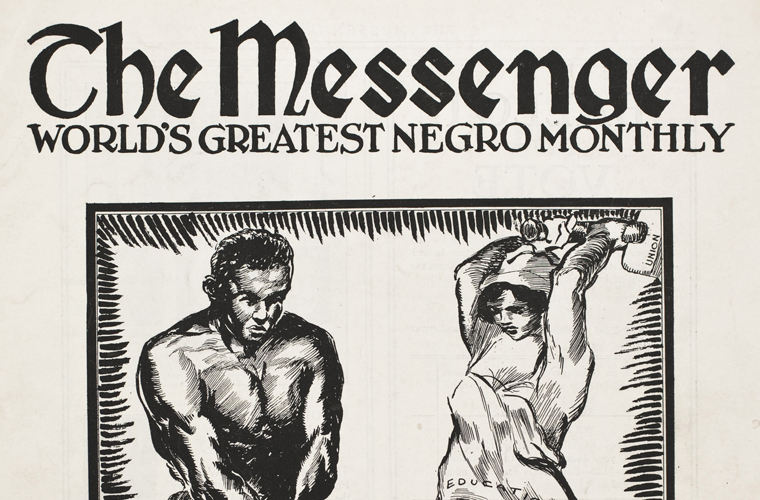

The Messenger, an independent magazine, was founded by labor activist A. Philip Randolph and economist Chandler Owen in 1917 with the help of the Socialist party. The Messenger alarmed both the white and black establishments by supporting socialism as well as the arrival of the “New Crowd Negro,” black intellectuals and political leaders who challenged both “reactionaries” like Booker T. Washington and civil rights leaders like W.E.B. DuBois. Among other things, the magazine opposed United States participation in World War I and encouraged armed self-defense by blacks against white mobs and lynchers. It was for these reasons that the magazine was initially termed “radical” by the United States government. In 1919, for example, the U.S. Justice Department claimed The Messenger was “the most able and the most dangerous” of all the publications it investigated.

In 1920, after the Socialist party had weakened significantly and the United States became more conservative, The Messenger began to distance itself from earlier radicalism and became more interested in promoting black worker unionization and opposing Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). The magazine also shifted editorial control when Owen decided to leave in 1923, and Randolph founded and became the first president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSPC).

George Schuyler and Theophilis Lewis gradually took over the editorial page. Under their guidance, The Messenger celebrated black entrepreneurship and the mainstream labor movement. The magazine added a “Business and Industry” page, as well as a sports page, and now carried articles directed at women and children. By 1925, The Messenger became the official organ of the BSPC when it began carrying union news and commentary.

Under Schuyler and Lewis, the paper also began to promote black art and artists. It carried articles about black culture, theater, and works by popular writers like Langston Hughes and Georgia Douglas Johnson. The magazine’s interest in the Harlem Renaissance was only heightened when Wallace Thurman briefly filled in for Schuyler in 1926. Unfortunately, The Messenger was forced to fold in 1928 when the BSPC could no longer afford to fund it.