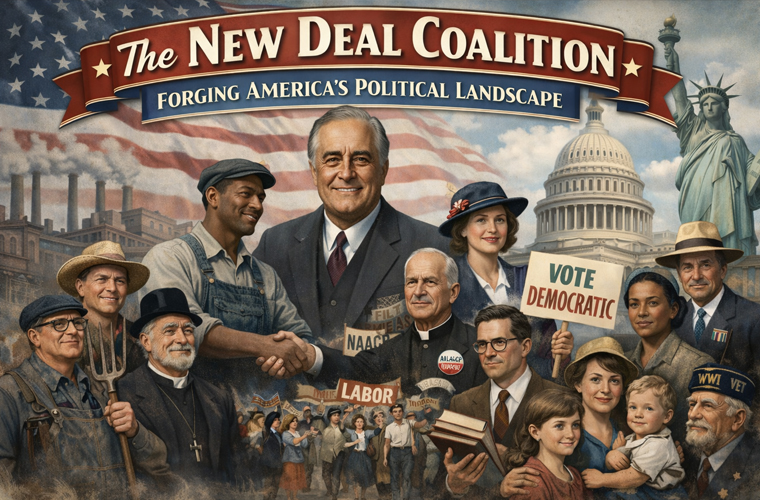

Forging America’s Political Landscape

In the depths of the Great Depression, as breadlines snaked through American cities and farms withered under dust storms, a new political force emerged to reshape the nation’s destiny. The New Deal Coalition, forged under President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR), was not just a voting bloc but a transformative alliance that propelled the Democratic Party to dominance for decades. This coalition united disparate groups—urban laborers, disenfranchised minorities, Southern conservatives, and progressive intellectuals—around a shared vision of government intervention to combat economic despair. Its rise marked the birth of modern liberalism in the United States, influencing everything from social welfare to civil rights. Yet, like all grand coalitions, it was fragile, ultimately fracturing under the weight of postwar prosperity and moral reckonings.

Origins in Crisis: The Great Depression as Catalyst

The seeds of the New Deal Coalition were sown in the economic cataclysm of 1929. The stock market crash triggered widespread unemployment—peaking at 25%—and bank failures that wiped out savings for millions. Herbert Hoover’s laissez-faire response alienated voters, paving the way for FDR’s 1932 presidential campaign. Roosevelt promised “a New Deal for the American people,” emphasizing relief, recovery, and reform through federal action. His nomination at the Democratic National Convention that summer galvanized a party fractured by urban-rural divides and ethnic tensions.

The coalition coalesced rapidly as New Deal programs rolled out during FDR’s first “Hundred Days.” Initiatives like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed young men, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) distributed aid, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) later built infrastructure while fostering arts and culture. These efforts appealed to those hit hardest by the Depression: industrial workers, farmers, and the urban poor. By blending economic populism with pragmatic governance, FDR transformed the Democratic Party from a loose confederation of Southern and Northern interests into a national powerhouse.

The Pillars of the Coalition: A Diverse Mosaic

At its core, the New Deal Coalition was a tapestry of unlikely allies, each drawn by tailored benefits and a common enemy in unchecked capitalism.

- Urban Ethnic Voters: Immigrants and their descendants in cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston—Catholics, Jews, and Italians—flocked to FDR. New Deal housing projects and labor protections addressed their overcrowding and exploitation in sweatshops. This group, once Republican-leaning, shifted en masse, providing crucial votes in swing states.

- Organized Labor: The coalition’s industrial muscle came from unions, especially the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which organized mass strikes in the auto and steel industries. The National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act, 1935) guaranteed collective bargaining, boosting union membership from 3 million to 9 million by 1941.

- African Americans: Historically loyal to the “Party of Lincoln,” Black voters began defecting amid the Depression’s racial inequities. While New Deal aid was uneven—Southern administrators often excluded Blacks—the programs still offered unprecedented federal support. FDR’s 1936 reelection saw Black support jump from 20% to 70% in Northern cities, thanks to figures like Mary McLeod Bethune in the “Black Cabinet.”

- White Southerners: The “Solid South,” a Democratic bastion since Reconstruction, remained loyal due to federal farm subsidies via the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and respect for states’ rights on segregation. This bloc provided congressional muscle but demanded concessions on civil rights.

- Farmers and Intellectuals: Rural Midwesterners benefited from price supports and electrification, while academics and writers—many employed by the WPA—championed FDR’s progressive ethos.

Electoral Triumphs and Policy Revolution

The coalition’s power was evident at the ballot box. In 1932, FDR won 57% of the popular vote and 472 electoral votes, sweeping Hoover aside. The 1936 landslide was even more decisive: 60.8% of the vote and all but two states, a testament to coalition unity. Democrats controlled the House (334-88) and Senate (76-16), enabling the Second New Deal’s crown jewels: Social Security (1935) and the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938), which set minimum wages and a 40-hour workweek. This dominance persisted through FDR’s third (1940) and fourth (1944) terms, defying the two-term tradition amid World War II. Postwar, the coalition secured Democratic presidencies under Harry Truman (1948) and sustained congressional majorities until 1952. It realigned American politics, making Democrats the party of government activism and Republicans fiscal conservatives.

Fractures and the Slow Unraveling

Prosperity bred complacency, and ideological rifts widened. World War II’s economic boom reduced Depression-era grievances, while suburbanization drew white ethnic voters to Republican suburbs. Labor’s militancy alienated moderates, and the Cold War’s anti-communist fervor targeted union leftists. The fatal crack was civil rights. Truman’s 1948 desegregation of the military spurred the Dixiecrat revolt, with Southern segregationists bolting to form a third party. Northern liberals pushed for change, but Southern Democrats blocked it. The coalition held tenuously under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, but Barry Goldwater’s 1964 GOP nomination—opposing civil rights—exploited Southern backlash. Johnson’s Voting Rights Act (1965) sealed the realignment: Southern whites migrated to the GOP, while African Americans solidified as Democrats. By Richard Nixon’s 1968 “Southern Strategy,” the New Deal order had crumbled.

A Lasting Echo: Legacy in Modern America

The New Deal Coalition’s dissolution birthed the Fifth Party System, but its spirit endures. It entrenched the welfare state—Social Security alone supports 67 million Americans today—and normalized federal roles in the economy and society. Recent analyses highlight its class realignment, offering lessons for addressing inequality through labor reforms. Critics argue it perpetuated racial inequities by accommodating Southern racists, delaying justice until the 1960s. Yet, as FDR declared in 1936, “Better the occasional faults of a government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.” The coalition’s bold experiment reminds us that politics, at its best, bridges divides to build a more equitable union. In an era of polarization, its story urges us to rediscover that unifying fire.