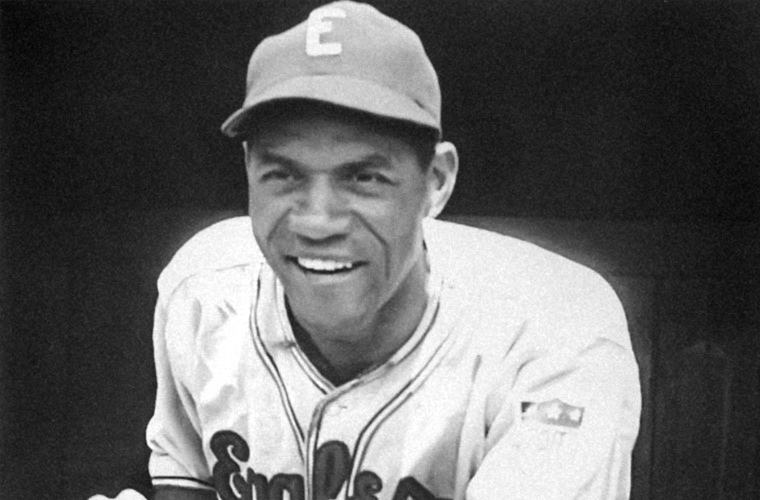

The best shortstop in black baseball during the 1930s and early 1940s, Wells was outstanding both in the field and at the plate. Possessing good range, sure hands, and an accurate arm, Wells compensated for a weak arm by a quick release and knowledgeable positioning based on a studied analysis of the hitters. His stellar defensive play earned him a spot in the Newark Eagles’ “million-dollar infield” in the late 1930s, where in addition to his defensive prowess he hit for averages of .386, .330, and .343 in 1937 39.

He began playing baseball on the sandlots of Texas and, while playing with San Antonio Black Aces in 1923, he was discovered by both Rube Foster of the Chicago American Giants and St. Louis Stars’ owner Dr. George Keys. Wells chose to sign with the Stars and began playing with the St. Louis club in 1924. Early in his career, through hard work and diligence, he made himself a good hitter, compiling averages of .378 and .346 in 1926-1927 while establishing a single-season record in the former year when he hit 27 home runs in 88 games. His hitting continued to sizzle as he annexed consecutive batting titles in 1929-30 with averages of .368 and .404. With Wells paving the way, the St. Louis Stars won Negro National League championships in 1928, 1930, and 1931.

His early stardom in St. Louis ended when the Stars folded along with the Negro National League, and Wells had a short vagabond period until settling with the Chicago American Giants. In Chicago he led the American Giants to consecutive pennants in two different leagues, capturing the Negro Southern League title in 1932 and the first flag of the new Negro National League in 1933. The latter season he hit .300, provided the leadership that sparked the team to the championship, and was selected to the West squad’s starting lineup in the first annual East-West All-Star Classic, where he contributed 2 hits to the West’s victory. His selection to the All-Star team established a tradition that was maintained for years, and in the eight All-Star games in which he appeared, Willie recorded a .281 batting average and a .438 slugging percentage.

In September 1934 Dan Daniel wrote in the New York World-Telegram, “Lloyd’s current counterpart is Wee Willie Wells of the Chicago American Giants. He is hitting .520, fielding 1,000 and stealing bases almost as regularly as Cool Papa Bell.” Two years later, in 1936, when the American Giants’ management had financial difficulties, Wells left Chicago for the Newark Eagles, where he joined Ray Dandridge, providing a pair of Gold Glove winners on the left side of the infield. Opponents threw at Wells so much that he became a pioneer in wearing a batting helmet. When Baltimore’s ace spitballer Bill Byrd hit him in the temple, knocking him unconscious, he was advised not to play for the remainder of the series. Disregarding the doctor’s advice, he played in the next contest, wearing a modified construction worker’s hard hat. The catalytic star continued playing with the Eagles for the remainder of the decade, batting .357, .386, .396, and .346 over the last four seasons.

Wells also spent several winter seasons in Latin American leagues, primarily in Cuba, where he had a .320 lifetime average in his seven years there. He played on the 1929-1930 championship Cienfuegos team. His final two seasons on the island, playing with Almendares, are indicative of his playing ability and team value as he won the team MVP in 1938-1939 and, in his farewell season, hit .328 to lead his team to the championship, earning a spot on the All-Star team and being voted the league’s MVP award. With the onset of the new decade, Wells traveled to Mexico, where the master shortstop became affectionately known as “El Diablo.” Records there show batting averages of .345 and .347 in 1940 and 1941 while playing with Vera Cruz, leading them to the pennant during the former season.

During the ensuing winter, he played his only season in Puerto Rico, batting .378 with Aquadilla. With the advent of World War II, rather than return to Mexico, Wells opted to return to the United States, and four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he wrote Abe Manley, offering to return to Newark as a player-manager for $315 per month. Manley was glad to have his star shortstop back, and Wells, an intelligent player and an excellent teacher of younger players, become a playing manager at Newark in 1942. As a manager, he was respected by his players, just as he had been respected as a player by his peers. Leading by example, he had a sensational season, hitting a resounding .361, being selected to Cum Posey‘s annual All-American dream team, and being identified as one of the top five players in the game when prospects qualified to go to the major leagues were discussed.

In 1943, after a disagreement with Mrs. Manley, he returned to Mexico, where he batted .295 with Tampico. The next year he batted .294, after replacing Rogers Hornsby as manager of the Mexico City ballclub after Hornsby allegedly served an ultimatum to get rid of Wells and three other blacks and was fired himself. Manley, wanting his star players back, had devised a plan to get Wells and Ray Dandridge back from Mexico by having their draft exemptions revoked. But Wells stayed in Mexico for two more years before he again returned to the United States, and although past his prime, “The Devil” still retained enough magic in his bat to hit for averages of .320 and .297 in 1945-46.

During the intervening winter, when an all-star team was picked to tour Venezuela, Jackie Robinson, then a rookie shortstop with the Kansas City Monarchs, was selected instead of the veteran Wells, who despite his age was still considered the best in the Negro Leagues. Soon afterward it was learned that Robinson had been signed by the Dodgers, and his presence on the all-stars was a way of showcasing him. Later, when Robinson was moved to second base with Montreal, Wells helped tutor him on the art of making the pivot.

In late May of 1946, Wells was released by the New York Black Yankees and signed by the floundering Baltimore Elite Giants to play third base. During the remainder of the 1940s, the wily veteran also served stints with Memphis and Indianapolis, batting .328 in 1948 at age forty-three. In the early 1950s, Wells traveled to Canada to assume the duties as playing manager with the Winnipeg Buffaloes, spending most of his final years in baseball in that country. He returned to the United States in 1954 as manager of the Birmingham Black Barons. When he finally hung up the spiked shoes, he left behind some impressive credentials. Against regular Negro League competition he recorded a lifetime .334 batting average, and against major leaguers, in exhibition games, he hit for a .392 average.

After retiring from baseball Wells worked in New York City at a delicatessen for thirteen years before moving back to Austin, Texas, in 1973 to help care for his aging mother. After she passed away, he continued living in the same house where he was reared, until he died from congestive heart failure in 1989. He was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997.