The American Colonization Society, 1816-1860

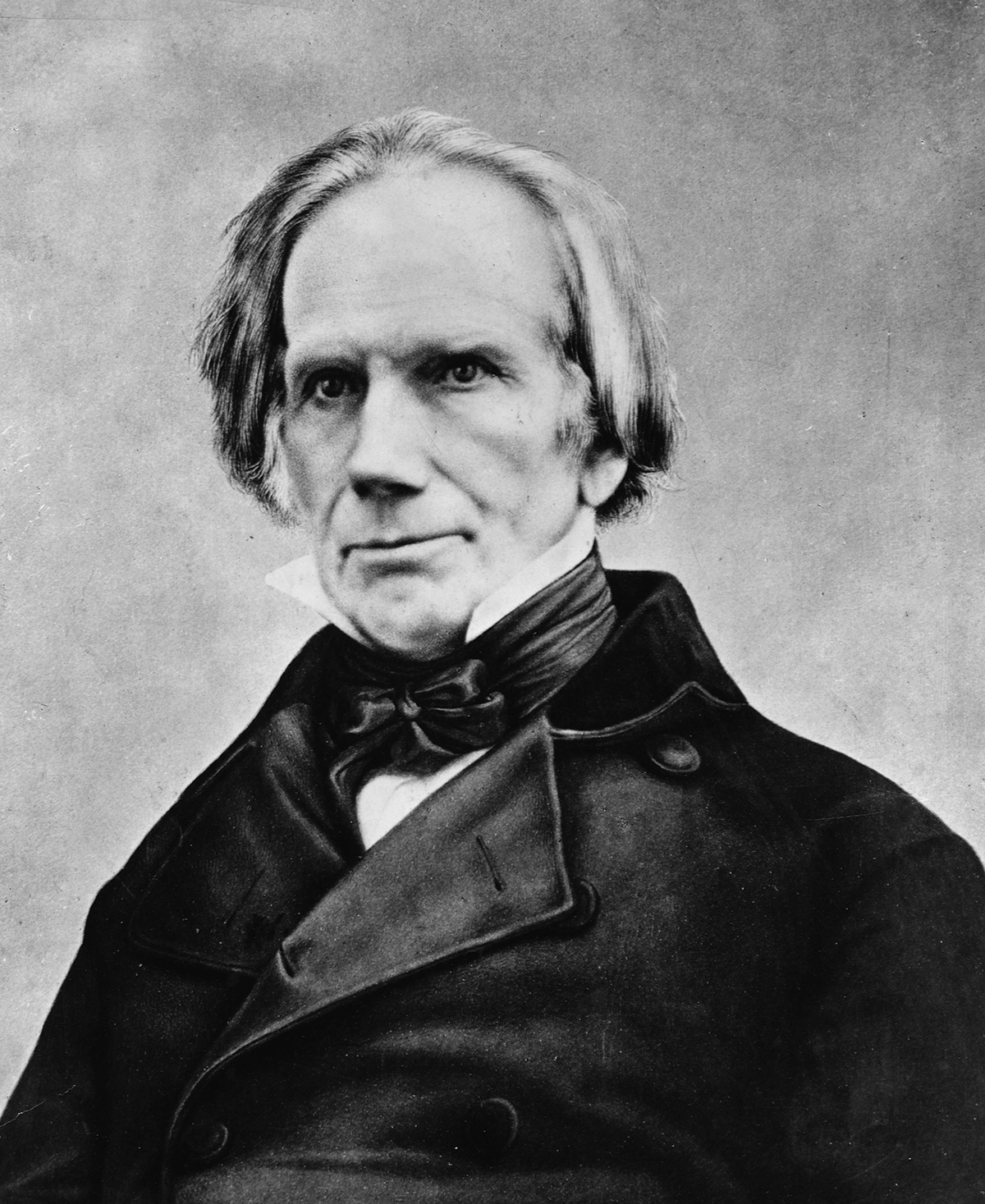

Speaking in the hall of the House of Representatives on January 20, 1827, Whig Party co-founder and Secretary of State Henry Clay affirmed the great potential of the American Colonization Society (ACS). Clay explained that it would be beneficial to transport free black people to Africa, arguing that in America, “they are in the lowest state of social gradation—aliens—political—moral—social aliens, strangers, though natives. There, they would be in the midst of their friends, and their kindred, at home, though born in a foreign land, and elevated above the natives of their country, as much as they are degraded here below the other classes of the community.”

The aim of the Society, Clay declared, “is to establish in Africa a colony of the free African population of the United States; to an extent which shall be beneficial both to Africa and America.” Not everyone agreed with Clay’s confident praise of Colonization. African Americans were the first to reject society’s plans to ship them away from their homes. A meeting of black Americans in Philadelphia in 1831 condemned the attempt to compel an “unprotected and harmless portion of our brethren” to leave their homes and go abroad, and claimed the United States as the “birthplace of our fathers…our own native land.” Colonizationists like Clay believed their project would benefit all involved, but they faced opposition from black and white abolitionists alike who saw their goals as a fundamentally conservative way to rid the country of its black population.

Henry Clay was not the first to propose the removal of blacks from America as a solution to the nation’s racial tensions, and wouldn’t be the last. In the early 1700s, slavery spread across British North America. Combined with urbanization, commercialization, and the transition to mixed farming in the Chesapeake region, The War for Independence challenged slavery with egalitarian rhetoric. Through a combination of gradual emancipation laws, and judicial, and legal processes slavery was slowly abolished in many northern states, beginning in 1777 in Vermont. Emancipation, however, did not mean that Americans were ready to accept an egalitarian multiracial society.

On the eve of the American revolution, in August 1773, Samuel Hopkins, of the First Congregational Church in Rhode Island, suggested sending ex-slaves as missionaries to Africa. Hopkins, like the colonization advocates who would follow him, saw slavery as a blemish on America’s image of a country of equality and liberty but was squeamish about the idea of racial mixing. Emerging from a revolution purporting to protect the values of equality and liberty for all men, with the lofty rhetoric of the Declaration of Independence, some Americans felt uneasy about the institution of slavery that existed in the new nation.

For Americans grappling with these contradictions, colonization provided a seemingly benevolent and ethical solution without granting African Americans full equality. In 1805, Thomas Branagan of Philadelphia proposed sending blacks to the American West, arguing that blacks were hopelessly contaminated by slavery and could not mix with whites.

Thomas Jefferson was an early advocate of colonization and believed that blacks and whites would never be able to coexist peacefully. He argued in Notes on the State of Virginia in 1785 that the “deep-rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections by the blacks; the real distinctions which nature had made; and many other circumstances will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.” As president, Jefferson reopened the issue of relocating free blacks and proposed Louisiana as a possible colony. (Ironically, Jefferson also probably had a long-term relationship with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings, who fathered her six children, and freed all of them before his death.)

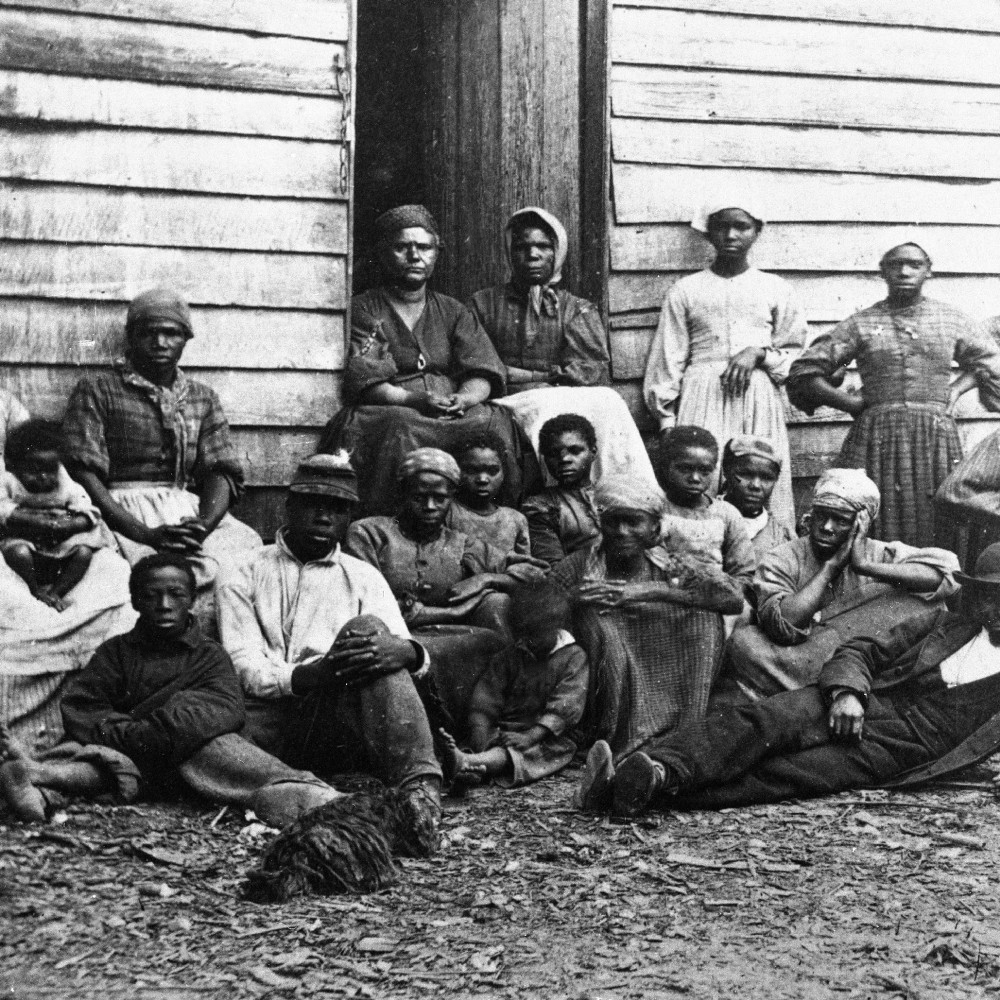

For a nation in which a large portion of the population was enslaved and black, fears of an uprising and retribution for whites were deep and constant, and racial mixing was reprehended. Pseudo-scientific theories argued that racial mixing would produce backward and inferior offspring, and fears of diluting the white race and complicating property and inheritance rules all influenced Americans’ detestation of racial mixing. Ideologies declaring Africans to be naturally inferior and fit for slavery eased the consciences of whites. Yet thinkers who purported that blacks liked their enslavement were met with contradictions when slaves rose up to contest their bondage.

In 1804, a successful slave revolution in Haiti made it the first black-led republic. After a slave revolt was uncovered in Richmond in 1800, and with news of Haiti circulating, Governor James Monroe wrote to President Jefferson proposing establishing a penal colony for “dangerous” blacks, removing them from society. Long before Robert Finley set events in motion to establish the American Colonization Society, ideas about deporting blacks and establishing colonies for them outside of America were gaining footholds in the young nation.

Beginning of the ACS

After the War of 1812, the United States embraced a new spirit of nationalism, the Second Great Awakening swept through the country, and benevolent societies focusing on individual self-improvement and missionary zeal popped up. In 1816, Charles Fenton Mercer, a white antislavery legislator from Virginia, and white New Jersey clergyman Robert Finley founded the American Colonization Society. These men appealed to both Northerners who disliked slavery but feared racial mixing, and Southerners who were uncomfortable with a free black population. The society grew in popularity and attracted the support of important politicians, benevolent society leaders, and church organizations from the north and south. Many of its supporters were people with income and education, like Francis Scott Key, composer of the Star-Spangled Banner, Vice President of the American Bible Society, and manager of the American Sunday School Union.

Former President Madison and Chief Justice John Marshall actively supported colonization, along with Whig politicians Daniel Webster, Edward Everett, Abraham Lincoln, and Henry Clay. In 1824, the Ohio legislature adopted resolutions in support of colonizing free blacks, and the legislatures of Pennsylvania, Vermont, New Jersey, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Connecticut, and Massachusetts endorsed Ohio’s resolutions. By 1825, the year that the society founded its journal the African Repository, colonization was a popular movement in America. Colonization seemed like a moderate and benevolent solution to the growing concerns over slavery’s future and what to do with the nation’s black population.

Liberia

The Society was successful in establishing a colony in Liberia. President Monroe, a supporter of colonization, used the Slave Trade Act to appropriate money for “returning” free black Americans to Africa. Although the first effort to establish a colony proved disastrous as disease decimated the settlers, Lieutenant Robert Stockton finally succeeded in gaining land (albeit, through extortion) on the Western Coast of Africa. Cape Mesurado was not a colony of the U.S. and had no legal status. By the late 1820s, after initial difficulties with surrounding native Africans, the colony was able to trade with local tribes.

The settlement was named Monrovia in honor of the president. Eugene S. Van Sickle, in his article Reluctant Imperialists: The U.S. Navy and Liberia, 1819-1845, explores the colonization movement from the perspective of American imperialism and expansion. American leaders in the federal government were reluctant to accept American expansion into Africa. Yet Colonizationists and U.S. Navy commanders, like Lt. Stockton, Lt. Perry, and Ashmun, without official governmental support, cooperated to promote the Liberian settlement and spread American imperialism. Sickle argues that Americans had begun to formulate expansionist ideas outside of North America earlier than is often recognized.

Protest

Most African Americans rejected colonization schemes from the beginning. With a few exceptions (such as the famous Paul Cuffee, a black sea captain who aided in transporting blacks to Africa), the freed African American community recognized colonization as harmful to their interests. In 1830, black leaders gathering in Philadelphia’s Bethel Methodist Church formed the “American Society of Free Persons of Colour,” and rejected colonization for legitimizing racist assumptions about blacks. The Convention decided to “discountenance, by all just means in their power, any emigration to Liberia or Hayti, believing them only calculated to distract and divide the whole colored family.” David Walker, the black author of the inflammatory 1820 pamphlet Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, spent the longest section of his Appeal arguing that colonization was simply a proslavery conspiracy.

He declared that colonization was a “plan got up, by a gang of slave-holders to select the free people of color from among the slaves, that our more miserable brethren may be the better secured in ignorance and wretchedness, to work their farms and dig their mines, and thus go on enriching the Christians with their blood and groans.” He scathingly criticized Henry Clay and other colonizationists. Walker belied colonizationists’ claims to return blacks to their own land, arguing that for blacks who grew up in America, whose parents and grandparents had been slaves, American land “which we have watered with our tears and our blood,” was the true “mother country” of slaves.

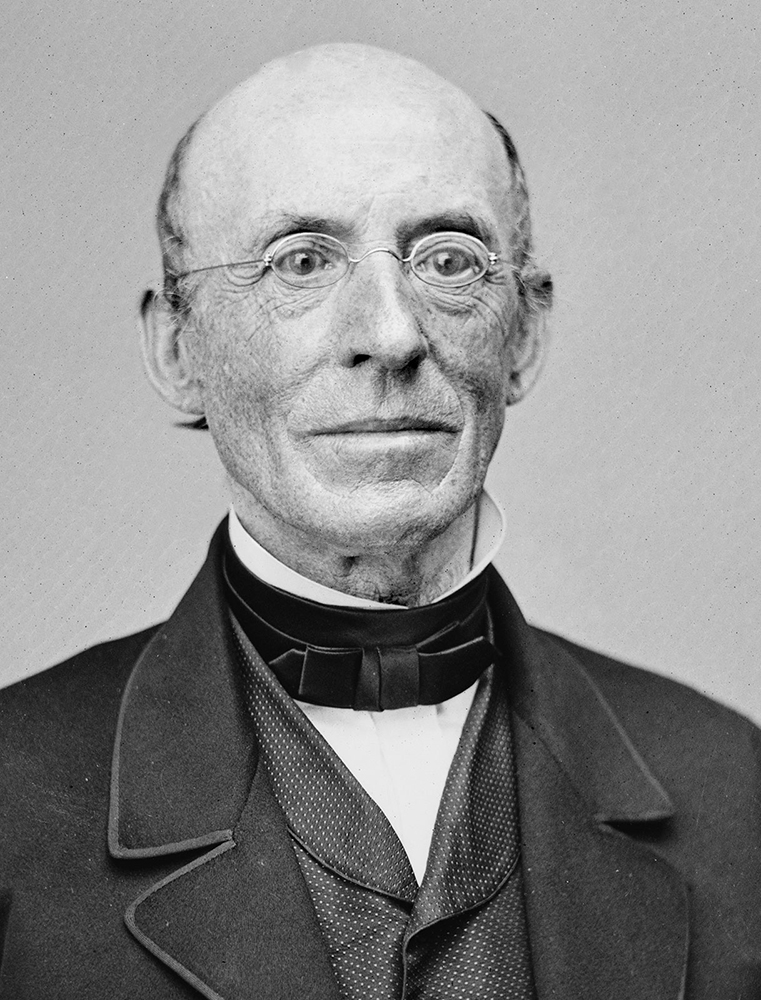

Indeed, Walker declared, “this country is as much ours as it is the whites.” The writings and arguments of the black community influenced William Lloyd Garrison, a white antislavery agitator, and in his Thoughts of African Colonization, he strongly condemned the organization. Garrison argued that colonization hindered the progress of antislavery, because it legitimized racism, and “it dissuades (slaveholders) from emancipating their slaves faster than they can be transported to Africa.” Within a few years, other white abolitionists followed Garrison in fighting against colonization. Abolitionists attacked the society for purchasing slaves and thereby legitimizing the institution of slavery by taking part in it rather than dismantling it. Abolitionists further criticized colonizationists for defending racism by arguing that white prejudice could never be overcome, while simultaneously strengthening slavery by ridding the south of its free black population.

Disintegration

After 1840, the Colonization Society, facing internal divisions and external attacks, hit hard times. Following the advent of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin and the skyrocketing profitability of cotton, and slavery, the South began to embrace depictions of its peculiar institution as a “positive good.” Southern slaveholders that had supported colonization began to denounce the schemes in favor of purely proslavery arguments. Between 1830 and 1840, the society faced economic difficulties, and internal divisions further weakened it. By 1834, the society was 45,645.75 dollars in debt. It lost support in the North as well as the South, as William Lloyd Garrison, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, James G Birney, Gerrit Smith, and other antislavery agitators abandoned colonization.

State organizations also began to separate from national organizations. The Colonization Society revived during the 1850s, as sectional crises and arguments over slavery intensified, but soon collapsed in the face of the Civil War. Proponents of colonization held that their plans were a moderate and reasonable solution to the threat of disunion. Speaking in Illinois in 1854, Abraham Lincoln declared that his first impulse was to “free all the slaves and send them to Liberia—to their own native land.”

Historical Debate

The American Colonization Society may not seem like a terribly controversial organization, but there has been a long historical debate regarding the extent that the society was, or was not, actually opposed to slavery and biological racism. From the 1920s to the early 1960s, most historians viewed the American Colonization Society as an antislavery organization, although conservative. From 1960 on, post-Civil Rights historians like Wilson Moses in 1998 and Lamin Sanneh in 1999 grew more critical of the society, and focused on its racism, concluding it was not truly an antislavery society.

Recently, historians have begun to reevaluate those conclusions, focusing on the society’s work manumitting slaves and weakening the South’s peculiar institution. Eric Burin, author of Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society, argues that although Negrophobia and fear of racial mixing were central to the colonization society, it nonetheless sought black emancipation. Focusing on the Pennsylvania chapter of the Colonization Society, Burin argues that the society’s goal was an end to slavery and that its supporters clung to colonization because they could not comprehend any alternative.

Burin draws attention to a number of times the Pennsylvania Colonization Society aided manumissions, such as when it raised money to free an enslaved family, the Corpsen family of Virginia, and send them to Africa. Burin argues that the colonization society depended on “dissonance-reducing cognition,” meaning that colonizationists suspended their recognition that the plan was unfeasible since it was far too expensive to transport the entire black population to Africa. They overlooked the contradictions in their own ideology.

Nicholas Guyatt, in Race and the Lure of Colonization, also argues that colonization was popular not because it strengthened racism and racial hierarchies, but because it allowed Americans to argue for the separation of the races without declaring that blacks were inferior. It allowed them to proclaim a future where blacks could emulate and reach equality with whites, on a separate continent. Guyatt argues that this line of thinking was the same type of theorizing that led to “separate but equal” doctrines at the end of the nineteenth century.

In his article, Guyatt juxtaposes the Indian colonization schemes with the African colonization schemes, arguing that both based their views on the assumption of nonwhite ability but necessary separation. He argues that although Americans were uncomfortable with blacks, colonization rhetoric did not reflect a hardening of racial boundaries, but instead reflected a mistrust of racial coexistence. Colonization relieved the “moral pressure” of egalitarian rhetoric by extending the same opportunities to nonwhites that had created America. Guyatt argues this reveals white Americans’ ability to fit prejudice and lofty idealism together, an ability that would allow the government to discriminate in separate but equal schemes for decades to come. Even today, decades after the Civil Rights movement, efforts to fully desegregate the nation’s institutions, neighborhoods, and schools, are painfully incomplete, echoing old ideologies that deny inherent racial inferiorities, but nonetheless, seek separation as a solution.

Whether the society truly intended to abolish slavery, as Burin and Guyatt suggest, it was nonetheless a deeply harmful institution. The lengths and depths of black protest against colonization are the best evidence of its harm.

Bruce Dorsey, in A Gendered History of African Colonization in the Antebellum United States, looks at colonization through another lens, analyzing the movement’s gendered character and ramifications. Dorsey argues that the Colonization Society was an intentionally masculine association. The society was located in Washington D.C., held its meetings in the House of Representatives, and operated among the nation’s political, and male, elite. Colonization was not only gendered in structure, but also in rhetoric. Colonization advocates declared that their work was an inherently manly endeavor.

They advertised their mission as following in the steps of the heroic history of colonization that had created contemporary America and appropriating images of rugged cowboys colonizing the American West. Colonization discourse argued that emigration would make “true men” out of African American men, implying that they had been so debased by slavery that only through colonization could they become men. As Dorsey points out, there were no equivalent ideas for women. The extension of this reasoning caused colonizationists to denigrate the manliness of blacks who refused to go to Africa. Colonization rhetoric also portrayed Africa as a woman and often used sexual images of male power colonizing a “rich” and “fertile” Africa. Beneath all of the colonization rhetoric was the attempt to separate blacks from whites, an issue that implicitly intimated the threat of amalgamation.

Most Americans feared the sexual mixing of blacks and whites, in part because amalgamation undermined the authority of white men, who could conceivably be replaced by black men in both the private and public spheres. In 1838, outraged that white women were mixing with black men, white anti-abolitionist rioters burned Pennsylvania Hall. Following the violence, the American Colonization Society held its largest colonization meeting ever in Philadelphia.

Dorsey concludes by turning to the startling lack of female colonizationists, made even starker by female domination of other benevolent societies of the time. Middle-class white women in antebellum America often surpassed men in their reform missionary work, yet in the colonization society where males formed over 200 auxiliary societies between 1817 and 1831, women supporters organized only nine. When white women did become involved, it was often highly conservative. Women like Catharine Beecher, who endorsed the colonizationist Philadelphia Ladies Association, decried the “gender transgressions” of abolitionist women. White abolitionist women who saw in the slave a mirror of their own oppression, sought to overturn the hierarchies of society, threatening white male privilege. Colonizationists, on the other hand, sought to maintain the status quo, protecting white masculinity and removing the dangerous black presence.

Conclusion

The American Colonization Society was founded during a turbulent time in American history. When the boundaries of citizenship, gender, and place were being tested and debated, when the future of slavery was hotly contested and the stability of the union was alarmingly unclear, colonizationists sought to find a moderate solution that would ease the tensions in the nation and their own consciences. While some historians argued that Colonization supporters were ultimately racist and did not seek to substantially change the slavery status quo, others argue that the colonizationists, while far from progressive, wanted both an end to slavery and freedom for blacks to realize their potential.

Colonizationists like Henry Clay may have truly believed in black potential, but their schemes nonetheless condemned black Americans to exile from a country they were fighting to claim as their own. The Colonization Society answered the myriad problems of antebellum America by seeking to strip blacks of their citizenship and their right to belong in the nation. The ramifications of their thinking would impact Americans long after the society’s disintegration.