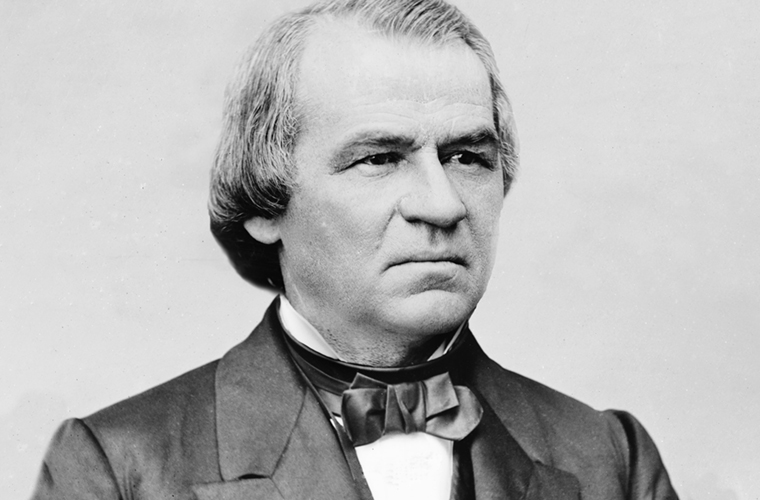

With the Assassination of Lincoln, the Presidency fell upon an old-fashioned southern Jacksonian Democrat of pronounced states’ rights views. Although an honest and honorable man, Andrew Johnson was one of the most unfortunate of Presidents. Arrayed against him were the Radical Republicans in Congress, brilliantly led and ruthless in their tactics. Johnson was no match for them.

Born in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1808, Johnson grew up in poverty. He was apprenticed to a tailor as a boy but ran away. He opened a tailor shop in Greeneville, Tennessee, married Eliza McCardle, and participated in debates at the local academy.

Entering politics, he became an adept stump speaker, championing the common man and vilifying the plantation aristocracy. As a Member of the House of Representatives and the Senate in the 1840s and ’50s, he advocated a homestead bill to provide a free farm for the poor man.

During the secession crisis, Johnson remained in the Senate even when Tennessee seceded, which made him a hero in the North and a traitor in the eyes of most Southerners. In 1862 President Lincoln appointed him Military Governor of Tennessee, and Johnson used the state as a laboratory for reconstruction. In 1864 the Republicans, contending that their National Union Party was for all loyal men, nominated Johnson, a Southerner, and a Democrat, for Vice President.

After Lincoln’s death, President Johnson proceeded to reconstruct the former Confederate States while Congress was not in session in 1865. He pardoned all who would take an oath of allegiance, but required leaders and men of wealth to obtain special Presidential pardons.

By the time Congress met in December 1865, most southern states were reconstructed, and slavery was being abolished, but “black codes” to regulate the freedmen were beginning to appear.

Radical Republicans in Congress moved vigorously to change Johnson’s program. They gained the support of northerners who were dismayed to see Southerners keeping many prewar leaders and imposing many prewar restrictions upon Negroes.

The Radicals’ first step was to refuse to seat any Senator or Representative from the old Confederacy. Next, they passed measures dealing with the former slaves. Johnson vetoed the legislation. The Radicals mustered enough votes in Congress to pass legislation over his veto–the first time that Congress had overridden a President on an important bill. They passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which established Negroes as American citizens and forbade discrimination against them.

A few months later Congress submitted to the states the Fourteenth Amendment, which specified that no state should “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

All the former Confederate States except Tennessee refused to ratify the amendment; further, there were two bloody race riots in the South. Speaking in the Middle West, Johnson faced hostile audiences. The Radical Republicans won an overwhelming victory in Congressional elections that fall.

In March 1867, the Radicals affected their own plan of Reconstruction, again placing southern states under military rule. They passed laws placing restrictions upon the President. When Johnson allegedly violated one of these, the Tenure of Office Act, by dismissing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the House voted eleven articles of impeachment against him. He was tried by the Senate in the spring of 1868 and acquitted by one vote.

In 1875, Tennessee returned Johnson to the Senate. He died a few months later.