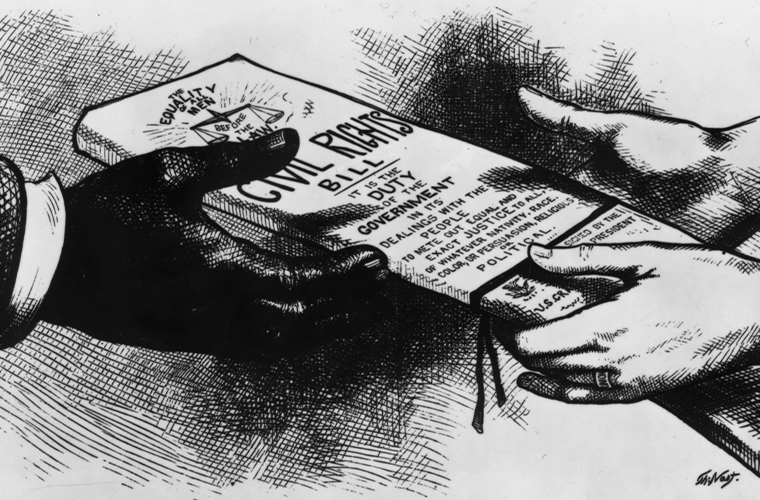

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27) was a momentous chapter in the development of civic equality for newly emancipated blacks in the years following the Civil War. The act accomplished three primary objectives designed to integrate blacks into mainstream American society. First, the act proclaimed “that all persons born in the United States … are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.” Second, the act specifically defines the rights of American citizenship:

Such citizens, of every race and color, and without regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, … shall have the same right in every state and territory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey the real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to the contrary notwithstanding.

Third, the act made it unlawful to deprive a person of any of these rights of citizenship on the basis of race, color, or prior condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.

CIRCUMSTANCES LEADING TO THE ACT

The roots of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 are traceable to the Emancipation Proclamation, delivered by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, which freed slaves held in bondage in the rebel states. In some ways, the proclamation appears to have been crafted to achieve certain military goals rather than advance the abolitionist movement per se. The declaration of freedom for blacks in the rebel states was intended to destabilize plantation society by encouraging slaves to challenge authority. Slaves forced into service as laborers on behalf of the Southern Army would become insubordinate. Plantations, drained of southern white men who were drawn into military service, were administered by the wives and elderly men. Not surprisingly, slaves would begin to challenge their authority in ways that served as a distraction to the war effort.

A second military goal was to secure a labor source to support the ever-expanding Union military efforts. Perhaps the most radical feature of the Emancipation Proclamation was the enrollment of free and newly emancipated blacks into military service. Black soldiers, though not considered equal to their white counterparts, nevertheless played a crucial role in constructing and holding fortified positions, and ensured the flow of goods along Union supply lines.

Although the proclamation was grounded in the military necessity, however, it quickly transformed the political landscape and strengthened opposition to the institution of slavery. As President Lincoln noted in December 1863, slavery had now become a “moral impossibility” in American society. The growing antislavery sentiment was confirmed by election results in 1864, which swept into Congress a core group of Republican leaders supportive of progressive Reconstruction efforts and protection of the rights and interests of blacks.

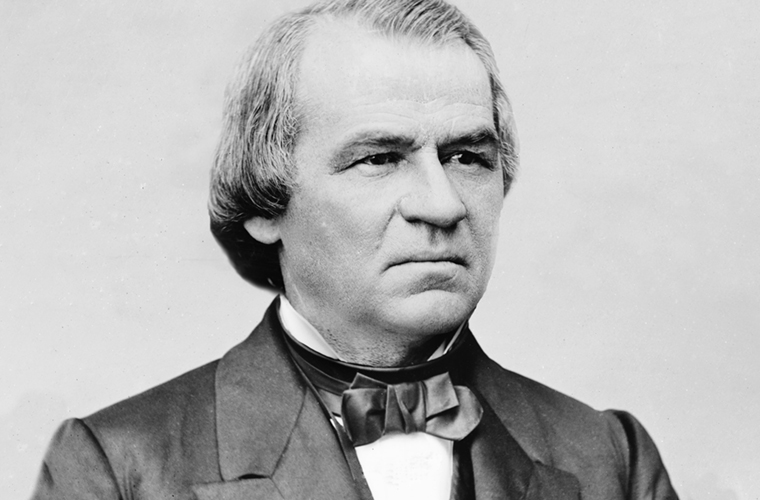

Andrew Johnson’s ascension to the presidency following Lincoln’s assassination signaled a turning point in the postwar Reconstruction efforts. Beginning in May 1865, President Johnson instituted a policy of Presidential Reconstruction designed to reconstitute the Union as quickly and painlessly as possible. Lincoln understood that the restoration of the Southern states to the Union was insufficient without the reconstruction of Southern beliefs and attitudes concerning slavery and the Southern way of life. But Johnson’s Reconstruction eased requirements for reentry into the Union and encouraged a defiant assertion of states’ rights and resistance to black suffrage. As the historian Eric Foner wrote in 1988, Johnson’s Reconstruction empowered white Southerners to “shape the transition from slavery to freedom and define blacks’ civil status without Northern interference”.

Not surprisingly, as whites regained social and governmental control from Union governors in accord with Johnson’s policies, they often undertook simultaneous efforts to severely limit access by newly emancipated blacks to the ordinary rights and liberties enjoyed by whites. Former confederate states—such as South Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama—passed and strictly enforced “Black Codes,” oppressive laws that applied only to blacks. Black Codes took a variety of forms, including mandatory apprenticeship laws, oppressive labor contract laws, strict vagrancy laws, and restrictive travel laws. Black Codes often authorized more severe punishment of blacks than of whites for identical conduct.

In addition to the Black Codes, Southerners engaged in private acts of discrimination and outright violence against freedmen. As Foner recounts, “the pervasiveness of violence [against blacks after the Civil War] reflected whites’ determination to define [freedom in their own way,] … in matters of family, church, labor, or personal demeanor”. Historian Randall Kennedy notes that this sometimes led to the beating or killing of blacks for such “infractions” as “failing to step off sidewalks, objecting to beatings of their children, addressing whites without deference, and attempting to vote”.

Although the Thirteenth Amendment had been ratified, and slavery constitutionally abolished, prevailing policies in the South threatened to make a mockery of the freedom granted to blacks. Under the leadership of Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction was formed to monitor and react to racially oppressive conditions in the South. The Joint Committee, in grappling with the question of “how the liberties of the black race were to be made secure,” ultimately arrived at the conclusion that additional measures needed to be adopted for the safety and elevation of newly emancipated blacks. One of those additional measures would become the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

LEGISLATIVE DEBATE

Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois introduced the bill that would later become the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Trumbull told the Thirty-Ninth Congress that the proposed legislation was needed to reinforce the grant of freedom to blacks secured by ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment: “When it comes to being understood in all parts of the United States that any person who shall deprive another of any right or subject him to any punishment in consequence of his color or race will expose himself to fine and imprisonment, I think such acts will soon cease.” Trumbull declared his intention to destroy the discriminatory Black Codes. Other Republican congressmen focused on the rights of blacks “to make contracts for their own labor, the power to enforce payment of their wages, and the means of holding and enjoying the proceeds of their toil.” If states could deprive blacks of these fundamental rights, as one Congressman remarked, “I demand to know, of what practical value is the amendment abolishing slavery?”

THE BILL’S LIMITED DEFINITION OF RIGHTS

Although radical for its time, it is important to understand the limits of the bill. The bill plainly sought to overrule the Black Codes by affirming the full citizenship of newly emancipated blacks and by defining citizenship in terms applicable to all persons. Under the bill, the designation as an American citizen meant that one possessed certain specific rights, such as the right to make and enforce contracts, the right to file lawsuits and participate in lawsuits as parties or witnesses, and the right to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold and convey real property. In defining citizenship in this manner, the act effectively overruled state-sponsored Black Codes.

At the same time, the act specified that these rights were “civil rights,” giving the first clear indication that, in the context of race relations, there were different levels, or tiers, of rights at stake. “Civil rights” at this time were understood in terms of property rights, contract rights, and equal protection of the laws. These rights were distinct from “political rights,” which involved the right to vote and hold public office, and “social rights,” which related to access to public accommodations and the like. Thus the bill reflected the common view that political participation and social integration were more or less “privileges” and not basic elements of citizenship.

Political rights would later be secured by the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment and the passage of civil rights legislation in 1870 and revisited nearly a century later in the Civil Rights Act of 1965. Congress’s attempt to grant social rights to blacks in the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was struck down by the United States Supreme Court as unconstitutional in The Civil Rights Cases (1883). However, Congress ultimately prevailed in granting social rights to blacks with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

PRESIDENTIAL VETO

Despite these apparent limits on the scope of protections afforded under the act, President Johnson nevertheless vetoed the bill. Johnson’s principal objection was a matter of procedure. In his veto message, he argued that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to enact the bill because “eleven of the thirty-six States are unrepresented in Congress at the present time.” Johnson also made clear, however, that he rejected the very idea of federal protection of civil rights for blacks, arguing that such a practice violated “all our experience as a people” and represented a disturbing move “toward centralization and the concentration of all legislative powers in the national government.”

Perhaps the most striking feature of Johnson’s veto message was its racism and inflammatory language. For example, Johnson objected that the act established “for the security of the colored race safeguards which go infinitely beyond any that the general government has ever provided to the white race. In fact, the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race.” Johnson also argued that blacks were simply unprepared to become citizens, at least as compared to immigrants from abroad, because, having been slaves, they were “less informed as to the nature and character of our institutions.” Johnson even mentioned the supposed threat of interracial marriage, suggesting that protection of the civil rights of newly emancipated blacks would somehow upset the established social hierarchy.

The effect of Johnson’s veto was to strengthen Republican opposition to his presidential policy. Congress overrode the veto and enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866. It also proposed the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution to remove all doubt about its power to pass this sort of protective legislation. Unlike the 1866 act, however, the Fourteenth Amendment ratified two years later, employs general language to prohibit discrimination against citizens and to ensure equal protection under the laws. Incorporating these protections into the Constitution marked a critical moment in the development of federal power over the states when it came to protecting the rights of citizens. To emphasize this new commitment to federal power, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was reenacted as section 18 of the Civil Rights Act of 1870. The 1870 act prohibited conspiracies of two or more persons that threatened a citizen’s “enjoyment of any right or privilege granted or secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States.” It also extended federal protection to voting rights for blacks.

THE ACT’S ENDURING SPIRIT

The spirit of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 lives on in modern anti-discrimination laws. One such law (42 U.S.C., section 1981) provides, in language derived largely from section 1 of the 1866 act, that “all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens.” This law is often relied on by plaintiffs alleging employment discrimination or discrimination in public or private education. Another law (42 U.S.C., section 1982), which was originally a part of section 1 of the 1866 act, “bars all racial discrimination, private as well as public, in the sale or rental of property,” and is frequently used in connection with housing discrimination lawsuits. A law (42 U.S.C., section 1983) granting private individuals today the right to sue for deprivation of civil rights by state officials echoes section 2 of the 1866 act as well as a subsequent act, the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act), which authorized civil and criminal penalties against rights violators in response to claims of lawlessness in the South.