Lewis H. Latimer’s father, George W. Latimer, was the first fugitive slave whose emancipation guided and influenced the American abolitionists of the 1850s. His flight to Boston, arrest, imprisonment, trial, and emancipation, as well as the numerous public meetings, held all over Massachusetts on his behalf,1 made him a cause celebre, fifteen years before the famous Dred Scott Decision. His supporters called it a “war on slavery.”

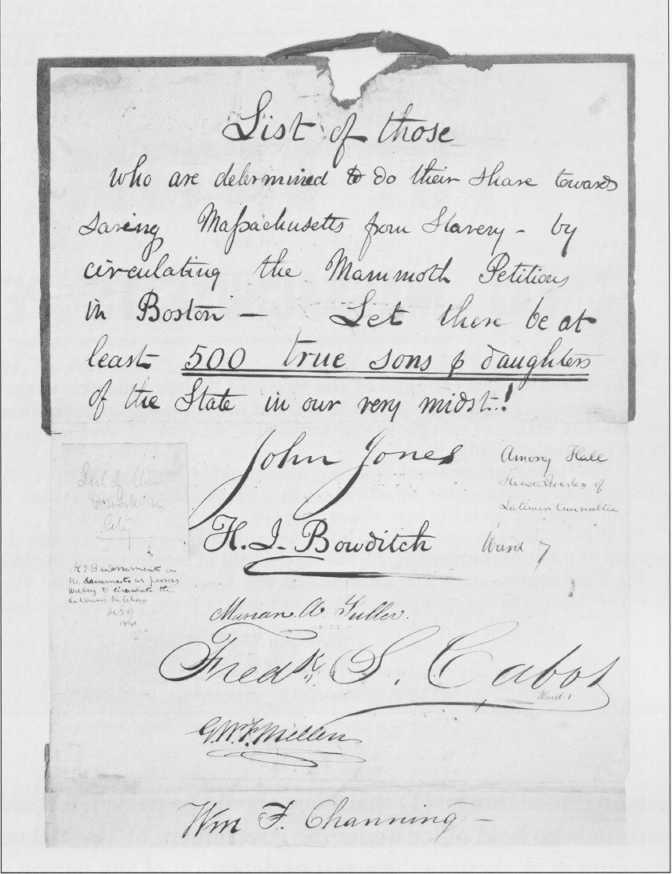

Supporters of the Latimer cause included Dr. Henry Bowditch, William Francis Channing, and Frederick Cabot. These men, described as “gentlemen of property and standing,” founded a newspaper called the Latimer Journal and North Star, which first appeared in Boston on November 11, 1842. Its purpose was “to meet the urgency of the first enslavement in Boston” and to rescue a fugitive slave from the custody in which he was detained. The editors of the Journal were determined to “discourage all intemperate and violent measures, even for the rescue of our citizens from enslavement.”

Critics claimed that the Latimer Journal “greatly excited and alarmed the credulous, vexed the irritable, inflamed the passionate, and exasperated those whose sympathies ran beyond their judgments.” Six issues appeared subsequently from November 11, 1842, to May 16, 1843, with a circulation of 20,000. The journal responded to a chain of events that had begun on October 4, 1842, when George Latimer, along with his wife Rebecca, ran away from slavery in Norfolk, Virginia, and fled to the North. Four days later, Latimer was recognized by William R. Carpenter, a former employee of Latimer’s owner, James B. Gray. Carpenter immediately communicated the information to Gray. On October 15th, the following ad appeared in the local newspaper:

RUNAWAY on Monday night last my Negro Man George, commonly called George Latimer. He is about 5 feet 3 or 4 inches high, about 22 years of age, his complexion a bright yellow is of a compact, well-made frame, and is rather silent and slow-spoken. I suspect that he went North Tuesday, and will give Fifty Dollars reward and pay all necessary expenses if taken out of the State. Twenty Five Dollars reward will be given for his apprehension within the State. . . .

James B. Gray2

Another ad confirms the fact that his wife, also a slave, ran away with him.

RUNAWAY from the subscriber last evening, negro Woman REBECCA, in the company (as is supposed) with her husband, George Latimer, belonging to Mr. James B. Gray, of this place. She is about 20 years of age, dark mulatto or copper-colored, good countenance, bland voice and self-possessed and easy in her manners when addressed.—She was married in February last [1842] and at this time obviously enceinte [pregnant]. She will in all probability endeavor to reach someone of the free States. All persons are hereby cautioned against harboring said slave, and masters of vessels from carrying her from this port. The above reward [$50] will be paid upon delivery to

Mary D. Sayer3

On October 18, James B. Gray arrived in Boston and caused Latimer, without legal process, to be arrested by police officers on a charge of larceny, and placed in the Leverett Street jail, where he began procedures to return Latimer to Virginia. On Sunday, October 30, a tumultuous meeting took place in Faneuil Hall “to provide additional safeguards for the protection of those claimed as fugitives from other states, or as slaves.” The excitement of the public meeting spread far and wide and the tone of indignation was deep and loud. This agitation, or “stimulants of popular passion,” not only excited the public mind in favor of Latimer but also increased the determination of the abolitionists to demand new legislative measures to protect the fugitive slave.

Free blacks were not simply bystanders to the affair. We see evidence of their “sense of freedom” and empathy for Latimer when a day after his arrest, nearly 300 black males assembled around the courthouse “to prevent the slave from being moved out of the city until word was pledged that Mr. Gray would take no steps not authorized by law.”4 After a number of disquisitions from various courts, interventions by a number of people (i.e., Samuel Sewall, W. L. Garrison, and J. W. Hutchinson), and after several weeks of incarceration, Latimer was cleared of the larceny charge and finally freed. A week before he was manumitted, the following interview was recorded between Latimer and one of the editors of the Latimer Journal:

I asked Latimer if he had ever expressed to Gray, or anyone else, a willingness to go back to Norfolk. He said “no, never, I would rather die than go back. Gray had just been there, trying to get me to say I will go back willingly. I turned my back on him and would not speak to him. He said if I would go back peacefully there would be no more trouble—he would like me out of jail and serve me well. I then turned toward him and said “Mr. Gray when you get me back to Norfolk you may kill me.”5

On November 18, 1842, Latimer was finally manumitted for $400 and forbidden from being returned to Virginia by Judge Shaw, following an evening of intense negotiations. Consider the following statement:

In the early part of this week, two petitions were gotten up and signed by many abolitionists, requesting Sheriff Eveleth6 to order Cooledge7 to discharge Latimer from the jail, and containing several threats to cause C’s removal from office for his abuse of power. This alarmed Cooledge, and on Wednesday evening, he notified Gray that he could not act as his agent any longer, and frankly states his reasons, viz: the prejudice these abolitionists were creating against him. Of this step the latter party must have been aware, for on that evening, Sewall8 called at the jail and directed Latimer how to act, should Gray attempt to take him into his own custody—to scream and raise an outcry, and then the negroes would rescue him. Fifteen or twenty negroes, too, watched the jail thro’ the night of Wednesday, to prevent Gray from removing his property. On Thursday morning, the counsel for the negroes in the riot case in the Municipal Court obtained a writ of habeas corpus to have L brought to the Court as a witness for the defense. On that day [November 17], an agreement was negotiated between a negro and Cooledge, for the purchase of the slave, and $800 was fixed as the price.

This was refused by the negro, who offered $650 for him, and upon Dr. Bowditch9 agreeing to pay that sum for George. Gray accepted it, and the parties were to meet at the jail office at 7 o’clock, to adjust the business. The hour came and brought the parties, but Dr. Bowditch stated that he had seen an order of the Sheriff directing Cooledge to discharge Latimer at 12 o’clock on Friday, and as Gray could not find a place strong enough to keep him from the negroes till the day of the hearing—and as he would of necessity be rescued, he should not pay anything for him; and thus backed out of his contract, and boasted on that evening to a friend of ours, that he had failed to fulfill his agreement. A negro minister, however, offered Austin10 $400 for Latimer, which was accepted; and at 10 o’clock on Thursday evening, the money was paid, and the slave was made a free man.11

The case did not end here, however. After lauding Latimer for running away from slavery, the Latimer Journal summoned:

Men of Massachusetts! Come up by the thousands to the city on Monday next. The victim is ready for the altar. His garlands are chains! His bracelets are handcuffs! His crown is a crown of thorns! Come ye up by myriads to see your brother.

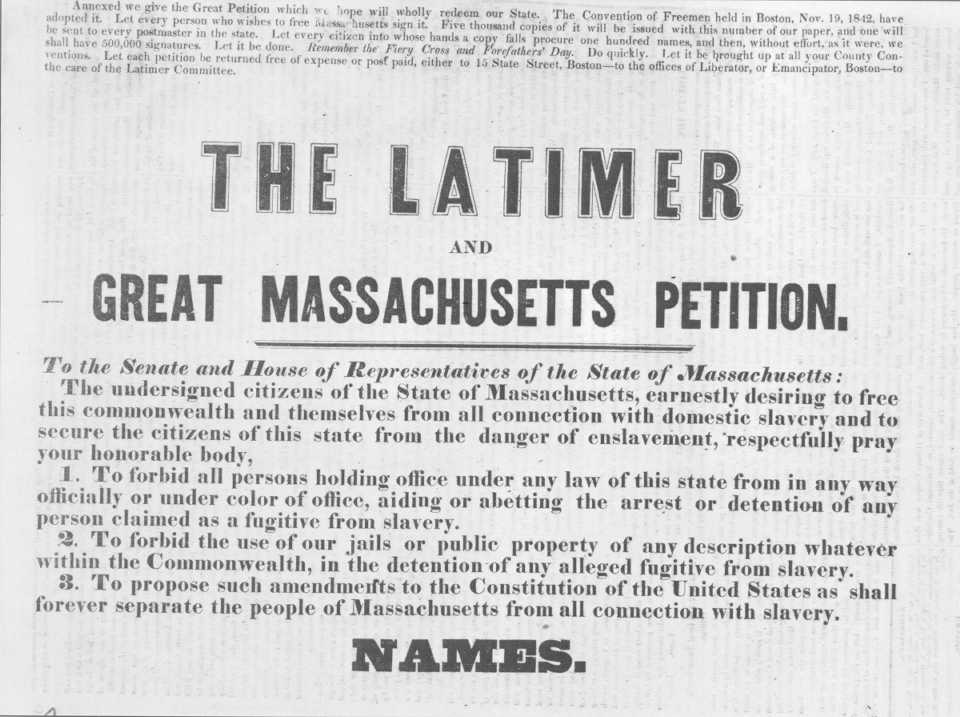

A petition signed by more than 65,000 citizens of the state of Massachusetts was presented to the legislature of Massachusetts demanding three things: (1) that a law should be passed, forbidding all persons who hold office under the government of Massachusetts from aiding in or abetting the arrest or detention of any person who may be claimed as a fugitive from slavery; (2) that a law should be passed forbidding the use of the jails or other public property of the state, for the detention of any such person before described; (3) that such amendments to the Constitution of the United States be proposed by the legislature of Massachusetts to the other states of the Union, as may have the effect of forever separating the people of Massachusetts from all connection with slavery.12 Subsequently, an act was passed for “the protection of personal liberty,” stipulating that “all judges, justices of the peace, and officers of the commonwealth, are forbidden, under heavy penalties, to aid, or act in any manner in the arrest, detention, or delivery of any person claimed as a fugitive slave.”13

The episode is a benchmark in the black struggle for freedom and a pivotal event in American history for another reason than its success in Massachusetts. A second petition proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, signed by nearly an equal number to the one mentioned, was sent to each of the senators and members of the Massachusetts House and also was forwarded to Washington. It stipulated that “direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states . . . according to their numbers of free persons . . .” and that “the number of representatives shall not exceed one for every 30,000.” After repeated attempts by John Quincy Adams to present it to the House, the petition was finally given over to the Speaker of the House, who referred it to the Judiciary Committee; there it remained until the close of the session when Barnard, the chairman, was unable to assemble a quorum of the committee to consider it.

Despite these significant episodes, there are few accounts of George W. Latimer’s life as a whole. The reasons for this are severalfold. First, although the events surrounding George Latimer’s life are fascinating, they are also complex and, because of a paucity of sources, difficult to piece together. Moreover, the few sources available do not project back to the years before he fled Virginia in 1842. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law (1850) and the Dred Scott Decision (1857) attracted comparatively more attention from scholars because of their direct impact on the events that led up to the Civil War. However, less than two months after Latimer was arrested, he provided some significant information about himself.