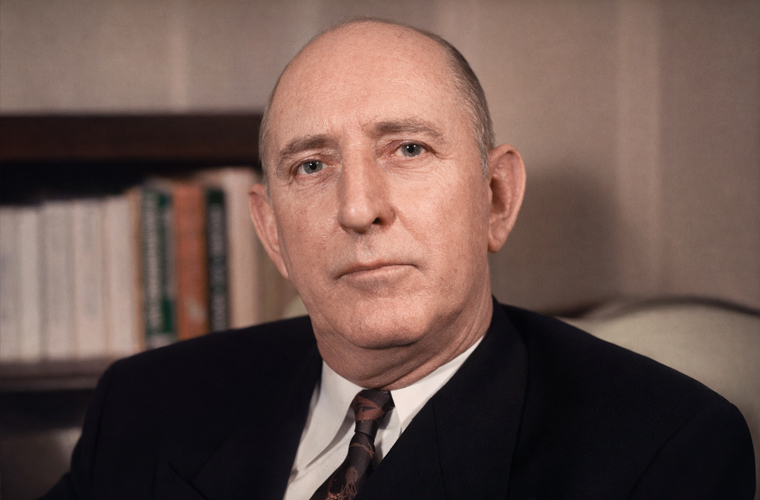

The Southern Sentinel

Richard Brevard Russell Jr., the longtime U.S. Senator from Georgia, embodied the contradictions of the 20th-century American South. A masterful legislator who steered defense policy and championed New Deal reforms, Russell wielded immense power in Washington for nearly four decades. Yet, his unyielding defense of segregation and filibusters against civil rights marked him as a formidable architect of Jim Crow’s endurance. Born into a family steeped in Georgia politics, Russell rose from statehouse speaker to Senate powerhouse, shaping national policy while safeguarding Southern traditions. His tenure, from 1933 to 1971, reflected an era’s tensions: economic progress intertwined with racial intransigence. As one biographer noted, Russell was “a man of iron will and unswerving loyalty to his region,” whose legacy remains a lightning rod in debates over reconciliation and remembrance.

Early Life and Education: Roots in the Peach State

Richard Russell Jr. entered the world on November 2, 1897, in Winder, Georgia, a small town north of Atlanta. He was the eldest son of Richard B. Russell Sr., a formidable figure who served as chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, and Ina Dillard Russell, a devoted homemaker from a prominent family. The Russells traced their lineage to early American settlers, but the Civil War’s scars lingered; their ancestral plantation had been ravaged during Sherman’s March to the Sea in 1864, instilling in young Richard a deep reverence for Southern history and resilience.

Money was tight in the Russell household, despite his father’s prominence. The elder Russell’s political ambitions—runs for U.S. Senate and governor—ended in defeat, teaching his son the harsh realities of public life. From an early age, Richard devoured books on the Confederacy, fostering a worldview that prized states’ rights and agrarian virtue. He attended local schools before enrolling in the University of Georgia School of Law in 1915. There, he thrived academically, earning his Bachelor of Laws in 1918 while joining the Phi Kappa Literary Society and honing his oratorical skills. World War I interrupted his studies briefly; Russell enlisted in the U.S. Army but saw no overseas action, returning to law with a deepened sense of duty.

Admitted to the bar in 1918, Russell joined his father’s Athens law firm, handling cases that exposed him to rural Georgia’s economic struggles. But politics beckoned early. At 23, he won a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives in 1920, representing Barrow County—a victory that launched a meteoric ascent.

Rise in Georgia Politics: Governor at 33

Russell’s statehouse career was a whirlwind of reform and pragmatism. Serving from 1921 to 1931, he chaired key committees on appropriations and agriculture, earning a reputation for fiscal discipline amid Georgia’s post-World War I woes. By 1927, at just 29, he became Speaker of the House, the youngest in state history. His leadership style—collegial yet commanding—bridged urban progressives and rural conservatives, streamlining government operations and advocating for public education.

The Great Depression tested his mettle. In 1930, Russell launched an improbable bid for governor, campaigning from Winder rather than Atlanta’s machine. Defying odds, he secured the nomination and general election, assuming office on June 27, 1931, as Georgia’s youngest chief executive. Facing 30% unemployment and bankrupt counties, Russell slashed the state bureaucracy from 102 agencies to 18, balanced the budget without raising taxes, and lured industries with tax incentives. He championed highway construction and rural electrification, laying the groundwork for federal New Deal partnerships.

One notorious episode defined his early governorship: the 1932 extradition battle over Robert Elliott Burns, whose memoir I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! exposed the brutality of the state’s convict leasing system. Russell decried the book as “slanderous” and pursued Burns’ return from New Jersey, ultimately losing in the courts but burnishing his image as a defender of Southern honor.

U.S. Senate Career: Power Broker in Washington

Russell’s national stage arrived swiftly. When Senator William J. Harris died in 1932, the 34-year-old governor won a special election, entering the Senate on January 12, 1933—just as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal dawned. Reelected six times (1936, 1942, 1948, 1954, 1960, 1966), he served until his death, becoming the Senate’s senior Democrat and “Dean” by 1969.

Russell’s early Senate years aligned with FDR’s agenda. A staunch New Dealer, he backed the “Hundred Days” reforms, securing Georgia billions in relief funds through the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps. He chaired the Appropriations Subcommittee on Agriculture, funneling aid to cotton and peanut farmers. His signature achievement, the National School Lunch Act of 1946, provided free or reduced-price meals to millions of children, a program still feeding 30 million daily and credited with boosting Southern nutrition.

Defense became his domain. As chairman of the Armed Services Committee (1951–1953, 1955–1969), Russell steered Cold War buildup, establishing bases like Robins Air Force Base in Georgia and advocating for a robust nuclear deterrent. He co-authored the National Security Act of 1947, birthing the CIA and the modern Pentagon. Later, as Appropriations Committee chair (1969–1971) and president pro tempore, he wielded the gavel with authority, briefing presidents on threats from Korea to Vietnam. Privately, he warned Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 against escalating in Southeast Asia, calling it “a hell of a mess.”

The Segregationist Stand: Filibusters and the Southern Manifesto

Russell’s legacy darkens here. A proud son of the Jim Crow South, he viewed federal civil rights incursions as existential threats to white supremacy. His opposition crystallized early in his Senate tenure, most notably in his fierce resistance to the Costigan-Wagner Anti-Lynching Bill of 1934–1935. Sponsored by progressive Democrats Edward P. Costigan of Colorado and Robert F. Wagner of New York, the bill sought to make lynching a federal crime, imposing penalties on mobs and complicit officials while allowing victims’ families to sue negligent counties. Amid a wave of lynchings—28 documented in 1933 alone—it represented a direct challenge to Southern impunity, where such violence enforced racial hierarchies with local authorities’ tacit approval.

Russell, then a freshman senator, emerged as a leading voice against it, rallying the “Southern Bloc” of Democrats who controlled key committees. He argued that the measure infringed on states’ rights, framing lynching as a “local criminal matter” rather than a civil rights violation under the 14th Amendment. In December 1934, he and allies like Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo threatened to filibuster FDR’s entire New Deal agenda unless the bill was shelved, leveraging their slim majorities to hold economic relief hostage. When the bill reached the Senate floor in 1935 as S. 24, Russell orchestrated a grueling six-week filibuster, delivering marathon speeches that invoked constitutional federalism and warned of “sectional strife.” The tactic succeeded: the bill died in July 1935, despite passing the House and garnering support from the NAACP and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Russell’s stand not only preserved Jim Crow’s violent underbelly but also signaled his rising influence, earning him the moniker “the most effective obstructionist in the Senate.”

This victory set the pattern for decades. By 1938, he blocked anti-poll tax legislation, preserving Black disenfranchisement. Post-Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Russell co-authored the 1956 Southern Manifesto, signed by 19 senators and 82 House members, decriing desegregation as “a clear abuse of judicial power” and pledging “massive resistance.” He filibustered the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, 1964, and 1968, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the 24th Amendment abolishing poll taxes—speeches stretching 75 hours, invoking constitutional federalism. “America is a white man’s country, yes, and we are going to keep it that way,” he once declared, rejecting social equality while insisting on “separate but fair” treatment.

Unlike firebrands like Strom Thurmond, Russell avoided overt racism, corresponding politely with Black constituents on issues like school lunches. Yet, his bloc diluted protections, stalling progress for decades. In 1964, he boycotted the Democratic National Convention after LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act, fracturing the New Deal coalition he once fortified.

Presidential Ambitions and Mentorship: Kingmaker’s Shadow

Russell eyed the White House twice. In 1948, he entered the Democratic primaries as a segregationist alternative to Truman, winning Georgia but faltering nationally. His 1952 bid was stronger: sweeping Florida and challenging Estes Kefauver, he garnered 294 delegates before Adlai Stevenson’s nomination. Refusing to back the party’s civil rights plank, Russell emphasized “local self-government” and Southern pride. A mentor to rising stars, he groomed Lyndon Johnson, guiding the Texan’s 1948 Senate win. Their bond soured over Vietnam and LBJ’s 1968 nomination of Abe Fortas as chief justice, which Russell helped derail amid ethics scandals.

Later Years and Death: Fading Influence

By the 1960s, Russell’s world shifted. The civil rights revolution eroded Southern Democratic power, and health woes—emphysema from chain-smoking—sapped his vigor. He dissented privately on the Warren Commission’s JFK findings, questioning the “single-bullet theory” but omitting it from the report. Retiring in 1971, he died on January 21 at 73 in Washington, D.C., from complications of his illness. Thousands mourned in Georgia; his funeral drew bipartisan tributes.

Legacy: Hero or Hindrance?

Richard Russell’s imprint endures ambivalently. The Russell Senate Office Building bears his name, as does Georgia’s tallest peak (once Blood Mountain). The school lunch program, expanded under his watch, combats child hunger nationwide. Supporters hail his economic stewardship—Georgia’s GDP tripled during his era—and defense acumen, which fortified the Free World.

Critics, however, decry his role in prolonging racial injustice. As leader of the “Southern Bloc,” Russell stalled, weakened, and defeated federal civil rights legislation for over three decades, delaying equality until the 1960s upheavals—exemplified by his pivotal defeat of the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which haunted civil rights advocates for generations. Recent reckonings, like 2020 calls to rename University of Georgia buildings, underscore this divide. Historian William Chafe called him “the defending champion” of segregation, a man whose eloquence masked moral blindness.

In Russell’s own words from a 1964 filibuster: “We will not yield… to those who would destroy our way of life.” Today, his story compels reflection: How does a nation honor builders who buttressed both progress and prejudice? As Georgia evolves, Russell remains a mirror to the South’s unfinished soul.