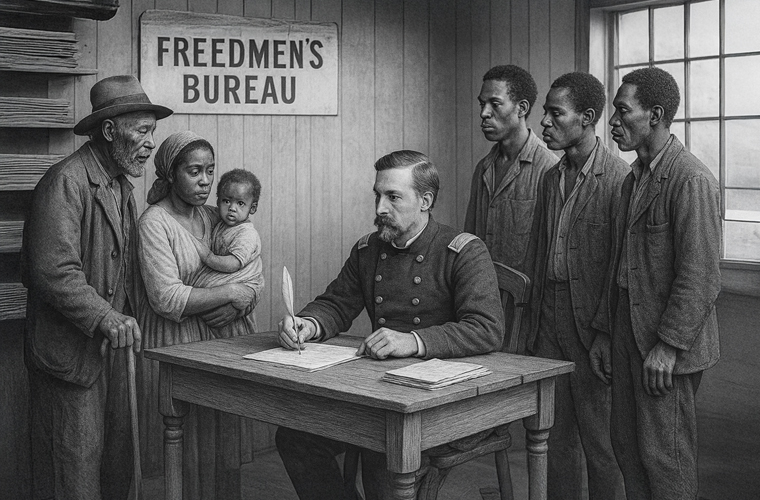

The Freedmen’s Bureau, formally known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, was a groundbreaking federal agency established in the aftermath of the American Civil War to aid millions of newly emancipated African Americans and destitute white refugees in the South. Operating from 1865 to 1872, it represented one of the first major efforts by the U.S. government to provide welfare and support during the Reconstruction era, addressing the immediate needs of those transitioning from slavery to freedom. Amidst a landscape of economic devastation, social upheaval, and racial tension, the Bureau tackled issues ranging from basic sustenance to education and legal rights. While hailed for its humanitarian and educational contributions, it faced severe limitations and criticisms, ultimately shaping the complex legacy of Reconstruction.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was created by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865, just weeks before the Civil War’s end, as part of the War Department due to the lack of independent funding and the military’s existing presence in the South. President Abraham Lincoln signed the legislation, building on recommendations from the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission of 1863. Its primary purpose was to provide temporary relief to “refugees and freedmen,” including food, shelter, clothing, and fuel for those left destitute by the war. This encompassed approximately 4 million formerly enslaved people, as well as impoverished whites in the Confederate states, border states, and the District of Columbia.

The Bureau’s mandate expanded through subsequent legislation, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill of 1866, which President Andrew Johnson vetoed because it infringed on states’ rights and fostered dependency. Congress overrode the veto, extending the agency’s operations and adding responsibilities like assisting Black veterans with bounties, pensions, and back pay. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the Bureau was overseen by assistant commissioners in each state, with sub-assistant commissioners and agents managing local field offices.

Major General Oliver Otis Howard, a Union Army veteran and abolitionist, was appointed as the Bureau’s first and only commissioner in May 1865. Known for his Christian humanitarianism, Howard led the agency through turbulent times, emphasizing education and moral upliftment. The organization relied on a network of military personnel, civilian agents, and partnerships with Northern missionary societies, such as the American Missionary Association (AMA). However, it operated with limited resources—never receiving dedicated funding—and controlled only a fraction of arable land for redistribution.

State-level operations varied: In Alabama, corruption marred aid distribution; Florida saw effective management under Thomas Ward Osborne; and Texas handled an influx of Black refugees. The Bureau’s records, now housed in the National Archives (Record Group 105), include letters, reports, labor contracts, marriage certificates, and censuses, providing invaluable primary sources for genealogical and historical research. The Freedmen’s Bureau implemented a range of programs to foster self-sufficiency among freedpeople, though constrained by budget and opposition. Between 1865 and 1869, the Bureau distributed over 21 million rations, with 15 million going to African Americans and 5 million to whites. It set up refugee camps, loaned supplies to planters, and provided immediate aid to prevent starvation amid post-war chaos.

Education was the Bureau’s most celebrated program. It spent $5 million to establish over 1,000 schools, enrolling more than 90,000 students by 1865, with attendance rates around 80%. Collaborating with missionary groups, it founded teacher-training institutions and historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Howard University (1867, named after Commissioner Howard), Fisk University (1866, named after General Clinton B. Fisk), Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University, 1865), and Hampton Institute (now Hampton University). The Bureau published textbooks promoting literacy and values, laying the groundwork for Black education during segregation.

The Bureau managed abandoned and confiscated lands but achieved limited success in redistribution. President Johnson’s policy of restoring lands to pardoned Southerners thwarted efforts, leading most freedpeople into sharecropping. Agents supervised contracts between freedmen and planters to promote a free-labor economy. They addressed exploitative Black Codes and gender dynamics, often encouraging women to work in fields but allowing exceptions for married women. The Bureau built hospitals and provided aid to over 1 million people, but efforts were hampered by epidemics, damaged infrastructure, and few doctors willing to treat Black patients.

It operated courts for civil rights disputes, legalized marriages from slavery eras (collecting records from 1861–1869), resolved apprenticeship issues, and helped reunite families separated by slavery. The Bureau also supported Black churches and assisted veterans with claims. The Bureau’s successes were profound in humanitarian and educational realms. It fed millions, provided medical care, and facilitated family reunions, helping freedpeople navigate freedom. Its educational initiatives created a network of schools and HBCUs that produced generations of Black professionals, teachers, and leaders, with HBCUs graduating 75% of Black dentists and significant portions of educators by the mid-20th century. It also legalized thousands of marriages and supported Black voting rights after 1867.

Despite its goals, the Bureau faced fierce opposition. Southern whites, including the Ku Klux Klan, targeted agents with violence, while President Johnson undermined it through vetoes and land restorations. Critics argued it fostered dependency, failed to redistribute land effectively (relegating freedmen to sharecropping), and had poorly organized courts that offered minimal civil rights protection. Inadequate funding, poorly trained personnel, and regional corruption (e.g., in Alabama) further hampered operations. Northern Democrats criticized it for allegedly making African Americans “lazy,” and state-specific issues, like unprosecuted murders in Louisiana, highlighted systemic failures.

By 1869, funding cuts and political shifts weakened the Bureau. Congress abruptly ended it in July 1872, transferring records to the War Department without informing Howard, who was reassigned to Indian affairs by President Ulysses S. Grant. The Freedmen’s Bureau’s legacy endures through its educational foundations, which influenced HBCUs and public education for Black Americans. Its records, digitized under the 2000 Freedmen’s Bureau Preservation Act and accessible via platforms like FamilySearch.org, aid genealogists in tracing African American ancestry. Though criticized for shortcomings in land reform and civil rights, it symbolized federal commitment to equality during Reconstruction, highlighting both the promise and perils of post-Civil War America.