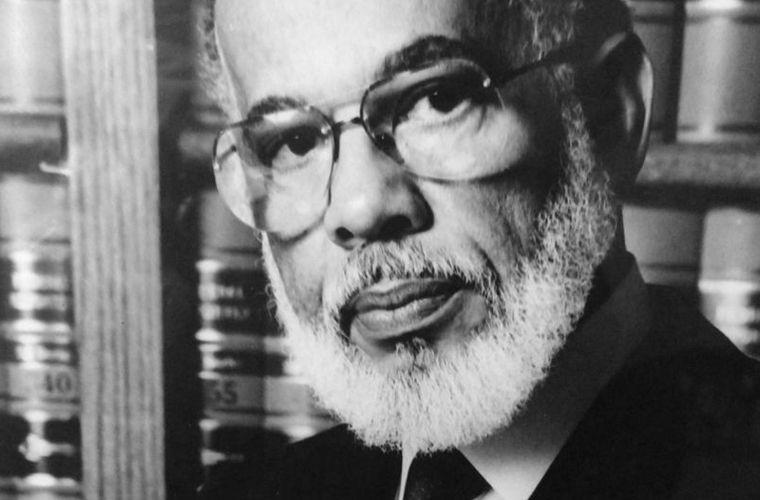

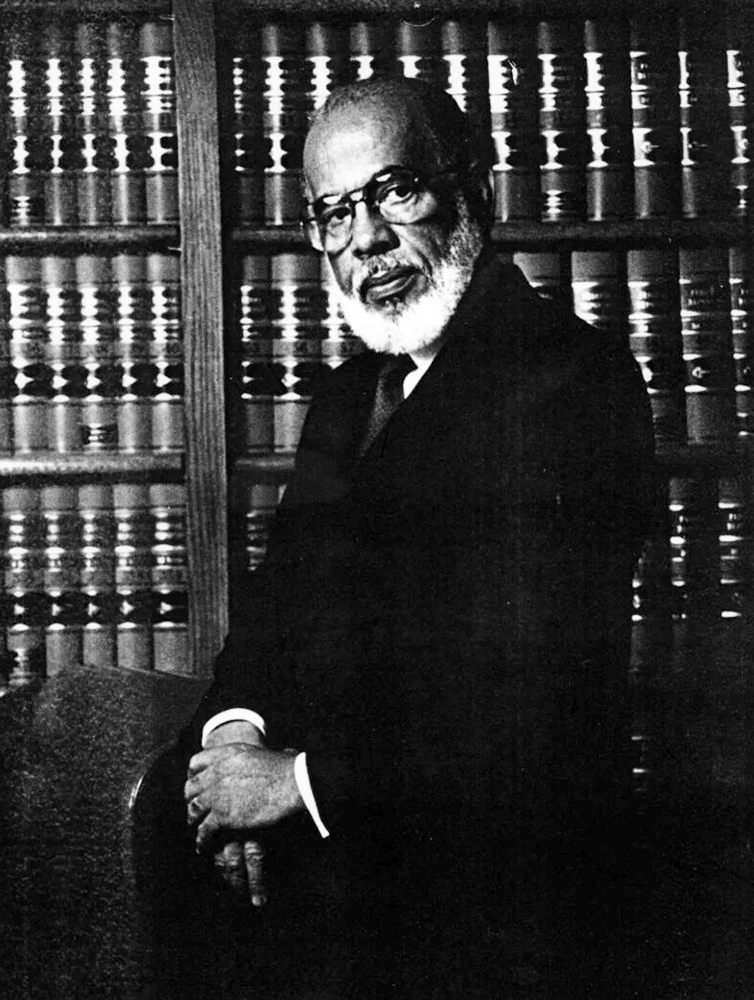

C. B. King was a prominent African American lawyer known for his courage, courtroom eloquence, and legal skills in the face of fierce and even violent opposition during the civil rights struggle in southwest Georgia. The first Black lawyer in the area, King was an inspiration to an entire generation of young law interns and civil rights activists.

Early Years

The third of seven sons, Chevene Bowers King was born in Albany in 1923 to Margaret Slater and Clennon W. “Daddy” King, both of whom were graduates of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute. Daddy King had earned Tuskegee expenses by working as a “buggy boy” for the institute’s celebrated president, Booker T. Washington. The drive for education, an important part of the King family’s priorities, became the path toward distinction for the young King and his brother Preston King. Ultimately the family’s involvement in the civil rights movement led to national and international prominence for four of the King’s sons, C. B., Preston, Slater, and Clennon.

Like his siblings, C. B. King was educated in Albany’s segregated school system. Following a brief period at Tuskegee and employment at a naval war plant in the Northwest, he served a tour of duty in the U.S. Navy. King then attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, graduating in 1949. Denied access to Georgia’s whites-only law schools, King enrolled at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. In 1951, the year before he received his law degree, King wed Carol Roumain; they eventually had five children.

Career

Back in Georgia, where he opened his law practice in the mid-1950s, King was one of only a handful of African American lawyers in the entire state and the only Black lawyer south of Atlanta who would take on civil and criminal cases. Frequently King’s reception in the courts was markedly uncivil. One of his legal partners in the 1970s, Herbert Phipps, who later served as Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals of Georgia, recalled the hostility his partner faced. Phipps noted that court officials did not want King in court and would try to make him leave or sit with the observers. Once, the judge would not halt proceedings at King’s request, though the case was going late into the night. When King asked for water, he was brought a bucket with a ladle. Characteristically, he made this a matter of court record, which later went up to the appeals court.

He stood his ground in the face of resentful opposition inside and outside the courtroom so firmly that he was once asked if he had a chip on his shoulder. “I beg your pardon,” he said, “I have the law on my shoulder.” Another time, King was addressed in court as “C. B.” instead of “Mr. King,” the conventional manner of address accorded to white men. He countered the incivility by referring to Police Chief Pritchett by his first name, Laurie.

In the earlier days of his practice reversals by a higher court were common occurrences for King, whose clients were often unjustly tried and sentenced before all-white juries. Success sometimes eluded him, as it did when he was unable to reverse the conviction of his brother Preston, who was sentenced in 1961 for draft evasion. A large part of King’s legal success can be attributed to his masterful use of language, which often dismayed courtroom adversaries. Sometimes his superior use of words provoked anger in opposing lawyers who were not sure of what he was saying. The civil rights activist and Georgia congressman John Lewis, defended by King when he was jailed in Americus during the 1960s, quipped that King used words that only King understood. King’s virtually photographic memory of the law put his opponents at a disadvantage. To the consternation of the judge and court, he would cite an appropriate law in minute detail, sending the clerks scurrying to the books to check on the accuracy of his statement. He was unfailingly correct.

The Civil Rights Era

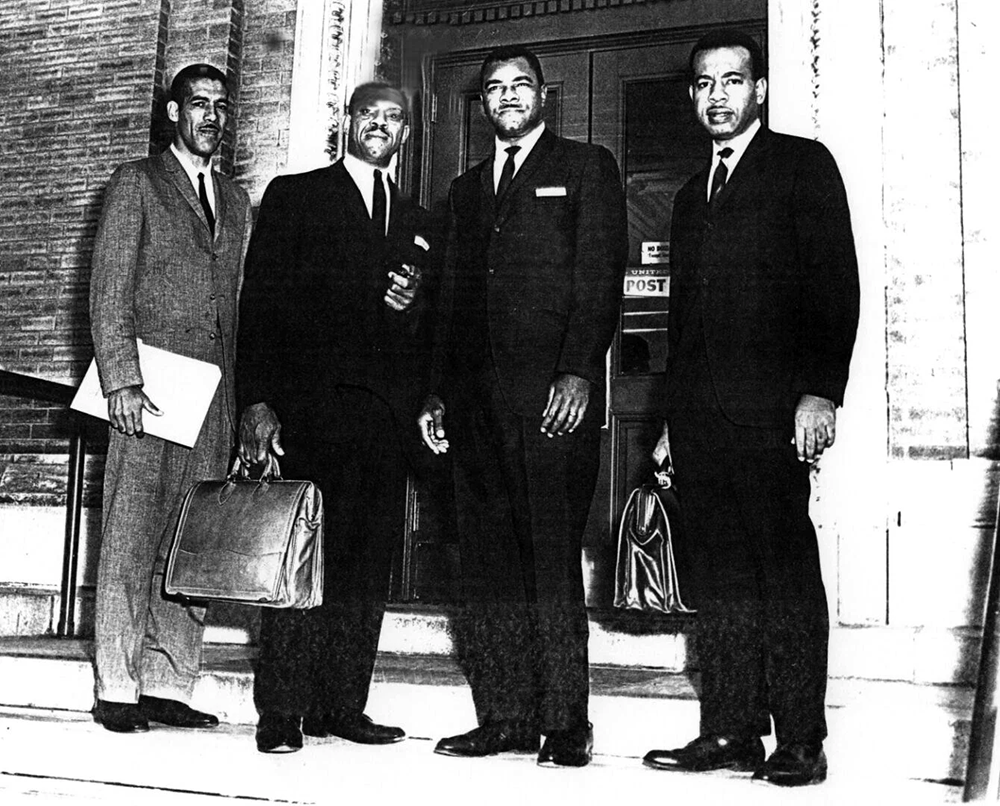

The 1960s brought a new set of complexities and challenges when ongoing struggles for equality of opportunity came to a head in southwest Georgia, as they did throughout the South. Civil rights protesters in the area looked to King, who aided them immeasurably. He was central to legal defense throughout the Albany Movement and beyond, defending Freedom Riders, the Americus Four, incarcerated civil rights protestors, and others caught up in the struggle for equality. Among his more famous clients were Ralph David Abernathy, Andrew Young, Martin Luther King Jr., and William G. Anderson, leader of the Albany Movement.

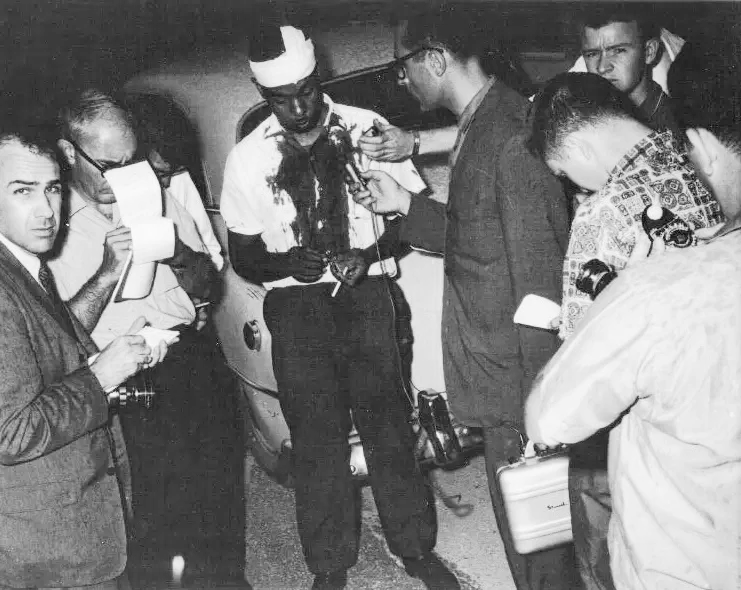

In 1962, when King visited the jail to check up on white civil rights protester Bill Hansen, whose white fellow prisoners had broken his jaw, Sheriff Cull Campbell assaulted King with a cane. A national photographer’s snapshot of the battered, bloodied, and the bandaged attorney was picked up by the wire services, made the first section of the New York Times, and was flashed around the world. These and other incidents inspired King in his fight to counter the forces that so often tried to stop his legal defense work. He worked hard to block literacy test requirements for voters and to integrate schools, polling booths, public accommodations, the pool of city employees, and the jury system. His efforts led to the 1968 Jury Selection and Service Act.

Political Career

King made two attempts to secure political office. His race to win a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1964, though unsuccessful, was a landmark effort, for he was the first Black candidate in Georgia to run for Congress since the Reconstruction era.

Nominated five years later, in 1969, by the state’s Black leadership, he became Georgia’s first African American candidate for governor. He was supported by Andrew Young, Hosea Williams, and Julian Bond. Harry Belafonte gave a benefit performance for the campaign. Although he did not win the governorship, his candidacy inspired large numbers of Black people to register, and their voting power ensured the election of several Black candidates for local and regional offices.

As a mentor for legal interns, King has had a far-reaching influence on the nation’s legal system. Law students came to his Albany firm from Harvard, Columbia, Yale, Howard, and Princeton universities, and from the University of Massachusetts and the University of California at Berkeley. A startling number of these young proteges underwent life-changing experiences under his tutelage, and a considerable number went on to become highly distinguished judges, members of Congress, and respected civil and environmental rights advocates. One 1963 Harvard intern, Elizabeth Holtzman, became the district attorney for Brooklyn, New York City’s comptroller, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, and a member of the congressional committee that investigated the Watergate scandal during Richard Nixon’s presidency.

In January 1988, only a few weeks before his death, the Georgia state legislature formally recognized his contribution to society. At the state capitol, he was presented the first Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award by the Georgia legislature and Governor Joe Frank Harris. As a culminating tribute to King’s legacy, in November 2002 the new federal courthouse in downtown Albany was named in his honor.