Jim Crow Laws in America and the American South:

A Comprehensive Examination

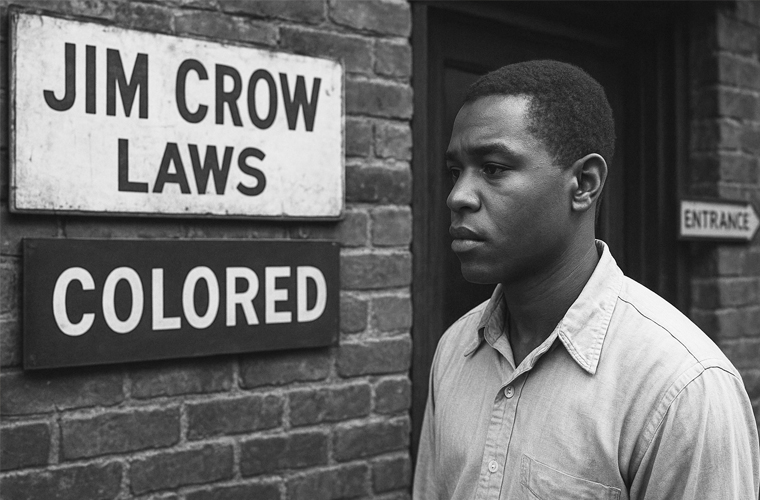

Jim Crow laws, a system of state and local statutes, ordinances, and social customs, enforced racial segregation and discrimination in the United States, primarily in the South, from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century. These laws institutionalized a regime of white supremacy, systematically disenfranchising, marginalizing, and oppressing African Americans while codifying racial hierarchies. Named after a derogatory minstrel show character, “Jim Crow” became synonymous with a legal and social framework that upheld racial inequality in nearly every aspect of public and private life. This article explores the origins, mechanisms, impacts, resistance, and eventual dismantling of Jim Crow laws, with a particular focus on their implementation in the American South.

Historical Context and Origins

The End of Reconstruction

The roots of Jim Crow laws lie in the post-Civil War era, particularly following the end of Reconstruction (1865–1877). After the Civil War, the Reconstruction period sought to rebuild the South and integrate newly freed African Americans into society through constitutional amendments and federal policies. The 13th Amendment (1865) abolished slavery, the 14th Amendment (1868) granted citizenship and equal protection under the law, and the 15th Amendment (1870) prohibited denying the right to vote based on race. Federal troops enforced these measures, and African Americans briefly gained political power, with Black legislators elected to Southern state governments.

However, Reconstruction faced fierce opposition from white Southerners, who resented federal intervention and Black political participation. By the late 1870s, Northern support for Reconstruction waned due to political compromises, economic concerns, and fatigue over Southern resistance. The Compromise of 1877, which resolved the disputed presidential election of 1876, led to the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. This withdrawal left African Americans vulnerable to white Southern efforts to reassert control.

The Rise of White Supremacy

With federal oversight diminished, Southern states began enacting laws to restrict African American rights. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan used violence and intimidation to suppress Black political and social advancements. Concurrently, economic systems like sharecropping trapped many African Americans in cycles of debt and poverty, resembling slavery in all but name. Against this backdrop, Jim Crow laws emerged as a legal mechanism to enforce racial segregation and maintain white dominance.

The term “Jim Crow” originated from a minstrel show character created by Thomas Dartmouth Rice in the 1830s. The character, a caricature of a Black man, was used to mock and dehumanize African Americans. By the late 19th century, the term became a shorthand for the legal and social systems that segregated and oppressed Black people.

Legal Foundations of Jim Crow

Plessy v. Ferguson and “Separate but Equal“

The legal foundation for Jim Crow laws was solidified by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In this landmark case, Homer Plessy, a mixed-race man, challenged a Louisiana law requiring segregated railroad cars. The Court, in a 7-1 decision, upheld the law, ruling that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional under the 14th Amendment. Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote the majority opinion, arguing that segregation did not imply inferiority as long as facilities were equal. In practice, however, “separate” facilities for African Americans were consistently underfunded, inferior, or nonexistent. This ruling provided a legal basis for segregation across the South and beyond, legitimizing Jim Crow laws and emboldening states to expand discriminatory practices. Justice John Marshall Harlan’s lone dissent, which warned that the decision would perpetuate racial inequality, proved prophetic.

State and Local Laws

Jim Crow laws varied by state and locality but shared the common goal of segregating and subordinating African Americans. These laws covered nearly every aspect of life, including:

- Education: Public schools were segregated, with Black schools receiving far less funding, outdated materials, and poorly trained teachers. For example, in 1915, South Carolina spent $13.98 per white student compared to $1.13 per Black student.

- Public Facilities: Train stations, buses, restrooms, water fountains, and parks were segregated. Signs reading “Whites Only” or “Colored” were ubiquitous.

- Voting Rights: Southern states used literacy tests, poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and other mechanisms to disenfranchise Black voters. For instance, Louisiana’s 1898 constitution included a grandfather clause that exempted white voters from literacy tests if their ancestors could vote before 1867, effectively excluding most African Americans.

- Housing: Restrictive covenants and redlining confined African Americans to specific neighborhoods, often with substandard housing.

- Marriage: Anti-miscegenation laws prohibited interracial marriage, with violations punishable by imprisonment.

- Criminal Justice: Black individuals faced harsher penalties and were subject to discriminatory practices like convict leasing, where prisoners were leased to private companies for labor.

By 1910, every Southern state had formalized segregation through such laws, creating a rigid caste system.

Social and Cultural Dimensions

The Role of Custom

Beyond formal laws, Jim Crow was enforced through unwritten social norms and customs. African Americans were expected to show deference to whites, addressing them as “Mr.” or “Mrs.” while being called by their first names or derogatory terms. Eye contact, assertive speech, or failure to yield the sidewalk could provoke violence. These customs reinforced a culture of humiliation and control.

Violence and Intimidation

Violence was a cornerstone of Jim Crow enforcement. Lynchings, a form of racial terrorism, peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1882 and 1968, approximately 4,743 lynchings occurred in the United States, with African Americans comprising the vast majority of victims. Lynchings were often public spectacles, attended by white crowds, including women and children, and rarely prosecuted. The Equal Justice Initiative has documented that many lynchings were triggered by minor or fabricated offenses, such as “disrespecting” a white person. White supremacist groups, including the Ku Klux Klan, used violence to intimidate African Americans and their allies. Night rides, cross burnings, and mob attacks targeted Black communities, churches, and schools.

Economic Impact

Jim Crow laws perpetuated economic disparities. African Americans were excluded from skilled trades, unions, and higher-paying jobs, often relegated to low-wage agricultural or domestic work. Sharecropping and tenant farming kept many Black families in debt, as landowners manipulated contracts to ensure perpetual obligation. By 1900, 75% of Black Southerners were sharecroppers or tenant farmers. Discriminatory practices like redlining limited access to homeownership, a key wealth-building mechanism. The Federal Housing Administration, established in 1934, often refused to insure mortgages in Black neighborhoods, further entrenching economic inequality.

Resistance and Opposition

Early Resistance

African Americans resisted Jim Crow from its inception. In the late 19th century, Black leaders like Ida B. Wells documented and publicized lynchings, exposing their brutality to a national audience. Wells’ investigative journalism led to international condemnation of racial violence, though she faced death threats and exile from the South. Black organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, challenged Jim Crow through legal action. The NAACP’s early efforts focused on anti-lynching campaigns and challenging voter suppression laws.

The Great Migration

Between 1916 and 1970, approximately six million African Americans left the South for Northern, Midwestern, and Western cities in the Great Migration. This mass movement was both an escape from Jim Crow oppression and a form of economic and social resistance. Migrants sought better jobs, education, and living conditions, though they often faced discrimination in the North as well.

The Civil Rights Movement

The mid-20th century saw the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, which directly confronted Jim Crow. Key events and strategies included:

- Brown v. Board of Education (1954): The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, declared school segregation unconstitutional, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” doctrine. The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, led by Thurgood Marshall, spearheaded this effort.

- Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–1956): Sparked by Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat, the boycott led to the desegregation of Montgomery, Alabama’s buses and propelled Martin Luther King Jr. to national prominence.

- Freedom Rides (1961): Interracial groups rode buses through the South to challenge segregated transportation, facing violent attacks but drawing federal attention.

- March on Washington (1963): Over 250,000 people gathered to demand civil rights, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

- Civil Rights Act of 1964: This landmark legislation outlawed segregation in public places and employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

- Voting Rights Act of 1965: This law banned discriminatory voting practices, such as literacy tests, and ensured federal oversight of voter registration in areas with a history of discrimination.

Grassroots activism, including sit-ins, freedom marches, and voter registration drives, played a critical role. Activists like Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and John Lewis faced imprisonment, beatings, and death threats, but persisted in dismantling Jim Crow.

Dismantling Jim Crow

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 marked the legal end of Jim Crow, dismantling the framework of segregation and voter suppression. Federal enforcement, including the deployment of federal marshals and the FBI, helped implement these laws, though resistance persisted in many Southern communities.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia (1967) struck down anti-miscegenation laws, further eroding Jim Crow’s legal remnants. However, social and economic inequalities persisted, as de facto segregation continued through housing, education, and employment practices.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The legacy of Jim Crow is evident in ongoing racial disparities in wealth, education, criminal justice, and health. For example, in 2019, the median wealth of white families was $188,200, compared to $24,100 for Black families, a gap rooted in historical policies like redlining and discriminatory lending. Mass incarceration disproportionately affects African Americans, with Black men incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of white men.

The Voting Rights Act’s protections were weakened by the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which eliminated federal preclearance for changes to voting laws in states with a history of discrimination. Since then, some states have implemented voter ID laws, felony disenfranchisement, and polling place restrictions, which critics argue disproportionately affect minority voters.

Jim Crow’s cultural legacy persists in debates over Confederate monuments, racial stereotypes, and systemic biases. Movements like Black Lives Matter draw parallels between historical injustices and contemporary issues, highlighting the enduring impact of Jim Crow.

Jim Crow laws were a deliberate and systemic effort to maintain white supremacy in the American South and beyond, affecting every facet of life for African Americans. Through legal segregation, economic exclusion, and racial violence, these laws entrenched inequality for decades. However, African American resistance, from early activism to the Civil Rights Movement, dismantled this oppressive system, reshaping American society. While the legal framework of Jim Crow has been dismantled, its legacy underscores the need for continued efforts to address systemic racism and achieve true equality.